Sound:

Value:

(Read about our ratings)

I can still remember it. Circuit City’s portable electronics section had a shoulder-height wall facing the door. It was one of the first things you saw when entering. Huge 36″ TVs on one side (left or right, depending on the store), and a display of CD players arranged on angled shelves on the other. Cheap Koss and no-name models at the bottom, some lacking any anti-skip memory, and the top-of-the-line Sonys and Panasonics at eye level. But then, on one side, there were these weird square devices that were too small to fit a CD. Too small even to fit a cassette. And they were expensive. There was a Sharp for $300 (that’s in 1990s USD) and a Sony for even more. But wait—was that a record button?

They were portable MiniDisc recorders. Launched in 1992, MiniDisc took a few years to gain any sort of traction and for prices to become more affordable for the mainstream. The promise was for “CD-quality” audio in a more portable and, most importantly, recordable format. You could buy pre-recorded discs too, if you could find them, but the real excitement was for something better than cassette but with the same portability.

As an audio nerd, and with my modest Circuit City employee discount, I was absolutely the demographic for such a weird device. I’d been making mixtapes for years. I was also an early adopter of Napster, thanks to my college’s fast-for-the-time T1 internet. In the summer of 1997, I paid around $285 for the very Sharp MD-MS702 you see here. That’s roughly $550 in today’s money, but I was working for the summer in the audio department in a busy store in a rich area, while living with my parents before going back to college and a far less interesting dining-hall job in the fall. So I could afford what would be my first piece of “high-end” audio gear, and it was amazing.

In the box

I don’t remember what headphones came with the MD-MS702, but searching online reveals a pair of earbuds that were almost certainly atrocious. They were the kind that hung on the concha, much like the ones that came with early iPods a few years later. I remember the fabric covering being scratchy, but that could have been any number of other earbuds of the era.

Two things stand out to me now. The first is the removable lithium-ion battery pack. Remember, this was 1997. Nearly all portable electronics, if they were rechargeable at all, had nickel-cadmium (NiCad) batteries. The high-end ones had nickel-metal hydride (NiMH). Lithium-ion batteries are everywhere now, from Teslas to true-wireless earbuds, but the ’90s were just the start of that revolution. The square AD-S31BT battery looked like a flattened AA, with “just” 800mAh of capacity. A modern li-ion battery of similar size would have roughly twice that capacity and cost a fraction. Either way, this one’s dead. Oh well. That battery is now 27 years old. I’m surprised it hasn’t exploded.

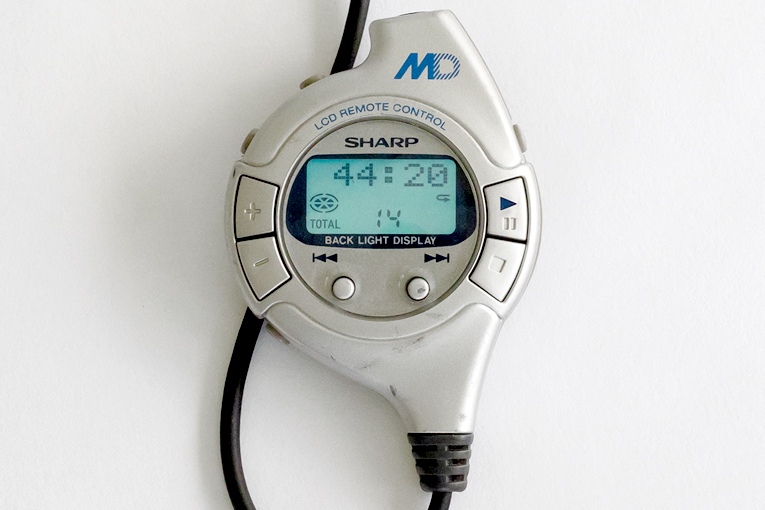

The other is the wired remote. You could connect any headphones you wanted to the Sharp, but the inline remote let you control volume, fast-forward/rewind, and more. It even had a small screen that duplicated the one on the player and glowed a lovely cyan. I’m not sure what this ’90s electroluminescent backlighting tech was, but it was a lovely color.

In the US, Sharp didn’t include the little battery pack that would hold an AA battery and extend playtime. I have no recollection of what that playtime was, but I still have the wall wart to power the unit, and I assume I had one for the car too. In the car, I’d play MiniDiscs I’d recorded from the analog output of my computer as it played downloaded MP3s. The Sharp’s analog output was connected to a cassette adapter in my ’87 VW Golf’s aftermarket Kenwood cassette deck, which lacked an AUX input. Yeah, sound quality was all over the place. The MD-MS702 did have an optical input, but I don’t remember if I had anything to connect that to. Definitely not on my Pentium II–powered PC.

Use

Despite an absolute sea of buttons on nearly every surface, using the MD-MS702 was pretty straightforward. Insert the disc, wait for it to read the TOC, and then start playing. It would take a few moments to switch tracks, since this involved physical movement of the laser mechanism. Being able to edit the TOC allowed you to do some clever and then-unique things like moving the track order around after you’d recorded the audio.

The LCD was fairly low resolution, so to see any title or track info, you’d have to wait for it to scroll. The same was true on the remote, but there, if you weren’t pressing buttons, a little fish would swim from left to right, trailing eighth notes.

Many of the buttons on the unit served double duty depending on whether you were playing or recording. You could adjust the bass via a button on the side, and on the back was a switch to lock out the rest of the buttons. On the right side was the mechanical lever to eject the disc.

Sound

MiniDisc, despite the marketing, was closely related to CDs. It used the same 780nm laser, so physics dictates they have a smaller storage capacity. Its way of maintaining the CD-length runtime was to use lossy compression. In this case, that meant Adaptive Transform Acoustic Coding, or ATRAC. When the 702 was launched, it still used the original 292kbps ATRAC codec from 1992. The history of ATRAC is worthy of an article in itself, but regardless of bit rates or intention, this was the 1990s. Compared to today, portable processing power was negligible. That means neither encoding nor decoding had any hope of being as good as what’s available now. Later versions improved the codec and even added a lossless version, but that was far in the future from the 702.

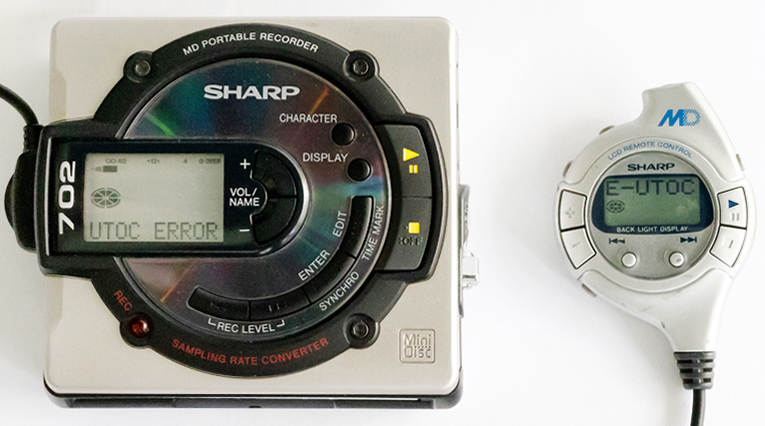

Unfortunately, sometime in the last few years the laser or its motor on my MD-MS702 went to the great diode in the sky. The unit powers on, tries to read the disc, and then gives the (as I’ve now learned) dreaded “UTOC” error. Goodnight, my old, faithful companion. You had a long life yet were short-lived, and you’ll never be replaced.

SoundX2

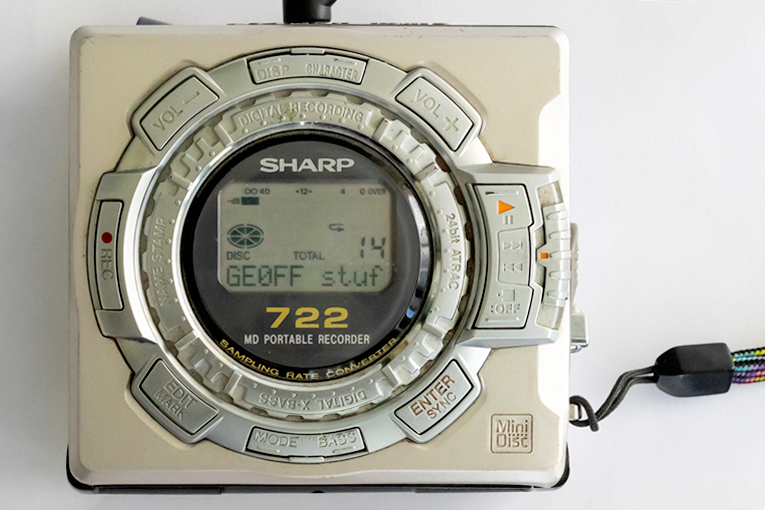

So anyway, here’s the Sharp MD-MS722 I just bought on eBay for $85. Amazingly, it still works. With a modern reviewer’s eye, I think the design of this newer player/recorder is a step backwards. I prefer the asymmetrical look of the 702. You wouldn’t think it’s possible, but the 722 is even busier looking, despite having roughly the same number of buttons. The silver-on-silver design is also a step back, but I’m probably biased. In its day, it probably looked more futuristic.

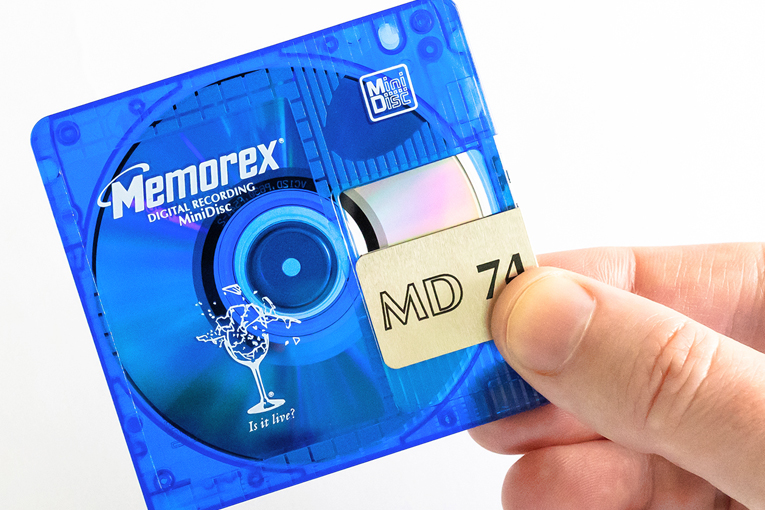

Now technically, I could have recorded FLAC audio from my PC onto MiniDisc and seen how it sounded. But what’s the point in that? To show a codec developed in the 1980s is inferior? No, this is a retro review. We’re going retro. I still have MP3-sourced mix discs I recorded in the ’90s because I apparently never throw anything out. So we’re going with those.

I wish I could say I had some in-era earbuds to use as well, but I guess I do actually throw some things out. So instead, I went the other way and used some Meze Advars (review pending). Using these to review MiniDiscs with analog conversions of MP3s is like using a SpaceX Falcon Heavy as a leaf blower.

The nostalgia that washed over me listening to these tracks was intense. So was the bass. I can’t speak to what kind of low frequencies those old earbuds were putting out, but through the Advars the 722’s setting of 3 was a bloated mess. My 702 was also set to 3 when I turned it on, so maybe I always had a bass problem? I switched it to 0.

A good example of the sound “quality” was “Mach 5” by the Presidents of the United States of America (II, ATRAC via MP3, Columbia Records / MiniDisc). While the guitars and vocals were fine, the cymbals had that infamous swishy-swooshy sound typical of MP3s of the era. It was easy to hear why compression had such a bad reputation when this was what so many people heard for years.

Weezer’s “Buddy Holly” (Weezer, ATRAC via MP3, DGC Records / MiniDisc) fared far worse. The cymbals were still a huge problem, but the vocals had noticeable sibilance, and overall it was just mush. It was so bad I had to remind myself what the actual recording sounded like, so I connected the Advars to my iFi Audio Hip-dac2 and checked the track via Qobuz. While the band’s self-titled debut (aka the “Blue Album”) is certainly not an “audiophile” recording, the cymbals sounded like cymbals, and the instruments and vocals were all identifiable in the soundstage.

Last up was Spacehog’s “In the Meantime” (Resident Alien, ATRAC via MP3, Rhino-Elektra / MiniDisc). This one sounded significantly better, and I think I know why. I owned this CD, and I remember ripping all the CDs I had to MP3 but at a minimum of 192 kbps. I don’t remember where I got those other tracks (cough Napster cough), and who knows what bit rate or terrible encoding process they had? The cymbals here actually sounded like cymbals, though they didn’t sound as natural as a modern encoding can sound.

Conclusion

No one at the time thought MiniDisc was some sort of gift to audiophiles. It was seen as a step up from cassette, being more portable and more easily recordable than CD. Its life was short. While technically supported by Sony for 19 years, its peak was really those few years before and after the millennium, before the rise of MP3. The iPod launched in 2001, but it took a few years to really dominate the market.

The legacy of MiniDisc might be what caused Sony to so badly stumble out of the Walkman era. Sony could have been the leader in portable media players. The Walkman brand still carried a lot of weight in the late 1990s. Its first MP3 players were atrocious, almost entirely because of a requirement to use Sony’s software to convert MP3s to ATRAC compression. With this slow and cumbersome process, Sony shot itself in the foot. By the time it eliminated this requirement, it was too late. The market was Apple’s.

While once popular in Japan, and to a lesser extent Europe and elsewhere, MiniDisc is largely just a footnote in the history of portable audio. Recordable CDs became cheap enough, MP3s became easier to find legally, and the iPod became a cultural phenomenon. As much as it pains me to say it, MiniDisc was a niche product.

However, as far as niche products go, it was awesome. A handheld, recordable, digital audio device in an era where such a thing was still the future. A future with the promise of a lithium-powered technological revolution of tiny, personal devices. A future filled with hope, as we sat atop the crest of a wave of late-’90s tech-boom prosperity. The Cold War behind us, the anticipation of a peaceful new century ahead. It was a moment, for sure.

. . . Geoffrey Morrison

Associated Equipment

- PC: iBuyPower Windows 10.

- Amplifier: iFi Audio Hip-dac2.

- Earphones: Meze Advar.

Sharp MD-MS702 MiniDisc Recorder.

Price: ~$575 in 2024 dollars.

Warranty: Yeah, right.

Sharp

100 Paragon Drive

Montvale, NJ 07645

1-800-BE-SHARP

Website: www.sharpusa.com