Every time I talk with my friend John Kellogg, I learn something new. John’s the vice president of Advanced Strategic Solutions for Xperi, parent company of DTS. That basically means he’s a liaison between Xperi and the music and movie production communities, a position he previously held for Dolby. John spends a lot of time in recording studios, and has a very good one of his own, too, so he’s always up on the latest trends in pro audio. Thus, when he recently told me, “Oh, the loudness war’s over; it’s all LUFS now,” I had yet another of the “Wait . . . what?” moments common to our conversations.

As John explained, the shift toward streaming music platforms and away from CD has increasingly made streaming services the gatekeepers between music producers and music listeners—a role formerly held by CD mastering and production services, and still held, to some degree, by radio stations. Once an artist or record company hands their digital music files to a streaming service, the streaming service then decides how best to present them.

John Kellogg

John Kellogg

Except perhaps for niche services catering to audiophiles, music streaming services strive to keep a broad spectrum of customers happy. One way they can do this is by adjusting the volume of individual music files so that playback level remains fairly consistent from tune to tune and album to album, so listeners don’t need to adjust the volume—something that’s especially important for curated playlists featuring multiple artists. Typically, this feature can be defeated—for example, Amazon Music HD and Spotify have an option to turn volume normalization on and off—but the apps usually have volume normalization on as a default.

To implement volume normalization, one measures the average level of a music file, then adjusts the volume for that file so its average volume matches a certain target, such as -15dBFS (i.e., 15 decibels below the maximum possible signal level, or full scale). Volume normalization has typically been done using RMS average level measurements spanning the full audible spectrum. More recently, volume normalization has been done using LUFS measurements, which were standardized in 2011. LUFS stands for “loudness units relative to full scale,” and it’s designed to reflect the fact that humans don’t sense all frequencies of sound equally—a theory embodied in the equal loudness contours, better known as the Fletcher-Munson curves.

LUFS incorporates K-weighting, which combines two filters. One filter compensates for the acoustical effects of the human head; it’s a shelving-type treble-boost filter that starts kicking in at 500Hz and levels off at +4dB above 4kHz. The other is a high-pass (bass roll-off) filter with a -3dB point at 60Hz and a slope of roughly -10dB/octave. By measuring average level with these filters in place, LUFS provides a more accurate assessment of how a human will perceive the average volume than a simple broad-band RMS or peak-level measurement can.

A LUFS value reflects the difference between full-scale (or 0dBFS) and the average weighted loudness. So a LUFS value of -15 is 15dB below full-scale, after the weighting filters are applied.

Back in the days when CD changers, early digital music file players, and radio stations served up our music, record producers and mastering engineers couldn’t be sure how loud the tunes preceding and following theirs on a playlist or radio program would be. But they all wanted their recordings to sound at least as good as everybody else’s—and as anyone who’s conducted controlled listening tests knows, the human ear tends to perceive a louder music source as sounding better. This resulted in the “loudness war” of the last 20 years or so, where mastering engineers (often at the insistence of record companies) would heavily compress a recording’s dynamic range so its average level might be just a few dB below full-scale. Thus, a tune would have an average loudness at least as loud as the previous or next tune—but its dynamic range would be so compressed that the impact of loud transients (encountered in drum hits, bass-guitar slaps, etc.) was lost and the music sounded much less lively and realistic.

LUFS targets for streaming services are typically somewhere in the mid-teens: for example, Amazon is -11, Apple Music is -16, and Spotify is -14. If a file mastered in the peak of the loudness war era for an average level of, say, -5dB RMS, is played through these streaming services with the volume normalization on, the service will bring the volume down to its LUFS standard. The file won’t sound any louder than any other, but it will still suffer the sonic degradation of extreme dynamic-range compression, and its peak loudness will actually be lower than that of a less-compressed file.

Knowing that their files will be played back with the same reasonable average loudness as everyone else’s gives recording and mastering engineers the freedom to incorporate more dynamic range into their productions. They may still want to master with higher LUFS values for CDs, which will necessitate more extreme dynamic-range compression. But considering that the CD is no longer the primary focus for most of the music industry, the record company may not wish to pay the additional mastering costs—and the CD will sound better at the streaming-friendly LUFS value. It’s quite an ironic twist that the popularity of streaming services may end up making CDs sound better, isn’t it?

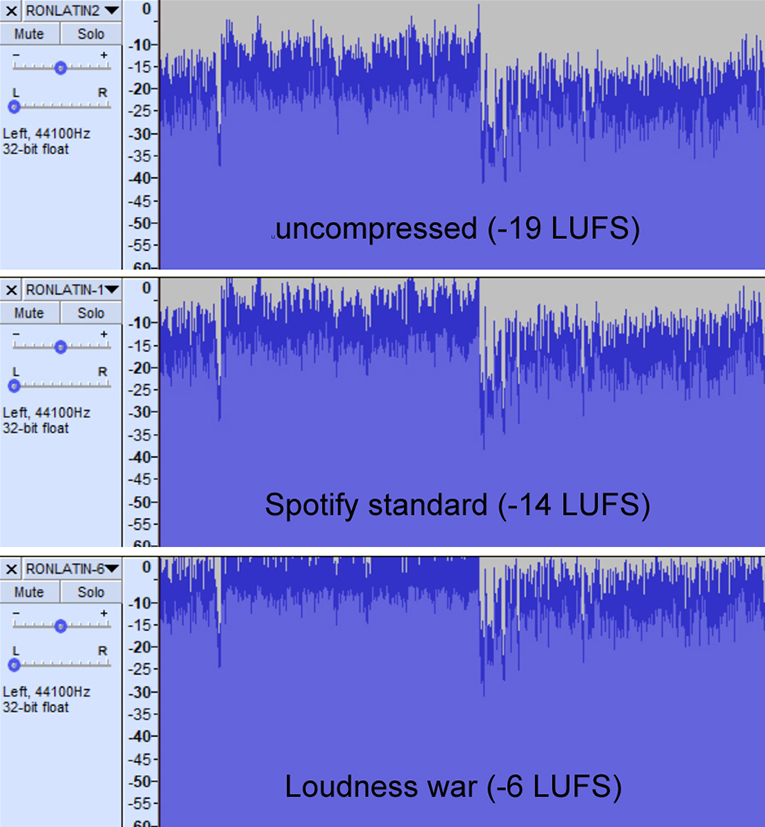

To see the difference among typical LUFS values, I ran a recording through the Waves WLM Plus Loudness Meter plug-in, which is used with Reaper digital audio workstation software, and adjusted the level and dynamic range compression to hit -14 LUFS (the Spotify target) and -6 LUFS (a value that might have been common in the heyday of the loudness war). The recording I chose was “Aprender,” a tune I recorded with saxophonist Ron Cyger for our upcoming album. The reason I chose this one wasn’t purely for shameless self-promotion; it was also because I needed an unprocessed mix that I knew hadn’t gone through dynamic-range compression.

The graphs here show the waveform for the first two minutes of “Aprender” at different LUFS values. The original, uncompressed mix (top graph) had a measured average loudness of -19 LUFS. I then applied a light 4:1 compression ratio so the signal peaks wouldn’t clip (i.e., exceed 0dBFS) and raised the level by 5dB, which gave me a Spotify-optimized average loudness of -14 LUFS (middle graph). Finally, I applied a heavier compression ratio of 9:1 and raised the compressor threshold to achieve average loudness of -6 LUFS (bottom graph), which is more typical of what we’d hear from loudness war-era masters.

You can see how the -14 LUFS version still has a good amount of dynamic range. In fact, the compression I used for that version is comparable to what I use for most of my music productions, and it’s similar to what I used for the soundtrack of the YouTube video in the link above. But the -6 LUFS version has very little dynamic range. I listened to it only briefly, but from a dynamic standpoint, it sounded something like what you hear when you play music from an AM radio station through a high-quality stereo system. Of course, what you see here represents just a quick attempt by someone with limited mastering experience to hit certain LUFS values. A professional mastering engineer would know the right tricks and tools to get better sound at -6 LUFS—but still, it’s probably not going to sound great.

I guess you can sum all this up by saying that the loudness war is over, and audiophiles won!

. . . Brent Butterworth