Take a look at the two camera lenses in the image below. It’s OK if you don’t know anything about photography. For this analogy to work, you can get the gist just from the picture. As far as the top-line specs go, these lenses are the same. They both fit Canon cameras, have a 50mm focal length (nicely between a telephoto and a wide angle), and are a “fast” f/1.4, which means they can take images in really low light and create a soft background when taking close-ups.

There are some key differences, of course. The big one has autofocus, is about 40 years newer, and fits modern cameras without an adapter. It takes razor-sharp images with impeccable color and contrast. It is, by all accounts, a vastly superior piece of glass, as photographers say. And yet I really like taking photos with the one on the right. It’s softer, the brightness of the image falls off severely at the corners, and manual focus could at best be considered “quaint” in 2024. Is it the best option for most photos? Not even remotely. What it has, though, is character.

This prehistoric lens, which is roughly my age to be fair, got me thinking about headphones. Earphones too, but for readability I’m going to call them all headphones. Is there a place in the entirely imaginary “best-of” pantheon for headphones that aren’t strictly “accurate”? The goal of all audio gear is to hear the music. If a headphone is fun to listen to, potentially increasing the enjoyment of listening to the music, isn’t that in some way valid? Is there a place for something that’s not accurate?

Well, to answer that question, I need to pose another.

What is accurate?

This is, frustratingly, harder to answer than you might think. To most enthusiasts, “accurate” means that the headphones reproduce frequencies evenly. With speakers, this is pretty much established science. Decades of research and testing have figured out how to get a pair of speakers to sound relatively flat in a well-treated room. That is a lot harder to do with headphones.

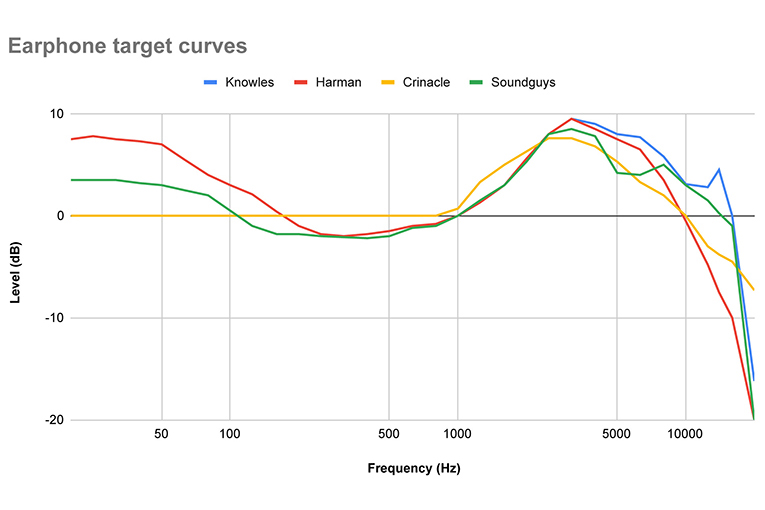

Due to how headphones interact with our ears, a design with a “flat” response, reproducing every frequency evenly, would sound atrocious. Accommodations must be made for the soft bits pressing against the headphones. There has been a lot of research along these lines, including countless listening tests and measurements, leading to things like the Harman target curve. As implied by the name, this target, or recommendation, is what exceptionally smart people, including Dr. Sean Olive, have found to get headphones to sound like good speakers in a decent room to most people.

Some people don’t like it, leading to many other target curves. That’s fine. At a minimum, it’s a place to start a conversation. From there, preferences vary, as do everyone’s ears. You might love the Harman curve, or you might like something else, but having a “baseline” target is laudable. So if a headphone matches that curve, is it “accurate”? For most people, arguably yes. For some people, not so much. To your ear, they might be so bright, so bassy, so . . . something that you find them boring, unpleasant, or just not your favorite. Is that wrong?

Which then raises the question, is accuracy the only goal if not everyone wants accuracy?

Bringing it all back home

Is there a place for good headphones that aren’t accurate? I feel like my hand is hovering over a third rail here. I’m going to climb way out on a limb and say, theoretically, yes. Or at least “yes within reason.” Obviously, there are plenty of headphones that are just wildly wrong. I’m not talking about headphones that would make any normal person wince after listening for two seconds. Headphones that bad are pretty rare, though, since, for the most part, all products get at least some amount of testing before release. Those aside, there are a lot of companies with some level of “signature sound.” Grado and Sennheiser come to mind, with many models broadly sharing some similar characteristics. If you don’t like those characteristics, are they “bad”? What about headphones that have extra bass, midrange, or treble? What if you like extra bass, midrange, or treble? To some extent, some of that is baked into the Harman curve, but while that target is certainly backed by research, it is admittedly just one company’s take.

I know some people whose idea of perfection is accuracy above all else. When it comes to their personal spending dollar, that goal is no more or less valid than someone who wants extra bass or any other sonic shifts from the mythical neutral. But the truth is, the best headphones will, by their nature, tend to be closer to neutral than not. This is the same reason why Harman, and before that those at the NRC, found that most people, in controlled listening, prefer neutral speakers over wildly sonically colored ones. It’s a more natural listening experience. In that approach to neutrality, however, there are infinite variations that could lead to some great-sounding headphones that, like that ancient Canon lens, have character, which can lead to notable and enjoyable listening experiences.

So is accuracy the only option? No, but it’s certainly a worthy place to start.

What do you think?

. . . Geoffrey Morrison