Yesterday at the IFA show in Berlin, Qualcomm announced aptX Adaptive, the latest in a line of audio coding technologies intended to improve the performance of Bluetooth audio. During the advance briefing I received early in August from Chris Havell, Qualcomm senior director of product marketing, I was excited about what aptX Adaptive might do for headphone sound quality, but also wondered about the reaction it may get in the audio community.

Except in a few rare cases, Bluetooth employs a codec to reduce the amount of audio data so it fits in the available bandwidth. Unlike the existing audio codec technologies used for Bluetooth, aptX Adaptive confronts the fact that people use their phones not only for phone calls and music playback, but also for gaming, TV, and movies. When you’re listening to music, you want the best possible audio quality, and it doesn’t matter if the sound is delayed by the roughly 200ms total latency typical of standard Bluetooth. But if you’re watching a movie, that fraction of a second could mean an actor’s speech doesn’t synchronize with his lip movement onscreen. If you’re playing a game, that fraction of a second could prevent you from responding to an aural cue in time to avoid a death blow from your opponent. The claimed approximate delay of 40ms for aptX Low Latency (plus whatever additional latency occurs in the Bluetooth transmission process) is small enough to minimize these problems.

Qualcomm says aptX Adaptive automatically adjusts its operation to achieve the best mix of low latency, high sound quality, and reliable transmission. According to Havell, “aptX Adaptive ‘just works.’ If it finds noisy RF [radio frequency] conditions that might make transmission unreliable, it scales down the bit rate to avoid breakup of the audio signal. It detects the nature of the content from the phone to give you the right audio experience and the highest resolution. The consumer doesn’t have to do anything. Most other codecs require you to manually step down to a lower bit rate to remove the breakup in situations when the transmission is unreliable.”

Havell said that aptX Adaptive automatically scales between data rates of 280 and 420kbps. In comparison, standard aptX’s data rate is fixed at 384kbps, and aptX HD at 576kbps; SBC, the standard codec for Bluetooth, can be implemented at different data rates, but its maximum is 345kbps.

I haven’t had a chance to evaluate aptX Adaptive yet, but I am eager to find out how well it can compensate for unreliable transmission. After all, the sound quality differences among codecs are almost always subtle and would usually go unnoticed, but the interruptions caused by a spotty Bluetooth transmission are impossible to miss and hard to tolerate -- as are large lip-sync errors in video and TV programs. (I can’t speak to the effects of latency on gaming, as the only games I play are puzzle-type games in the Tetris mold.) If aptX Adaptive can fix these problems, I’ll be thrilled.

So why was I left wondering what kind of reaction aptX Adaptive will receive in the audio community? Because most people’s ideas about audio codecs are driven purely by the data rates they support; they assume that the higher the data rate is, the better the sound. By these standards, some might think that aptX Adaptive could be a step down from aptX HD, or even from regular aptX or Bluetooth SBC. I worry that they might dismiss a technology that could deliver a clear, readily observable benefit, something that a “better-sounding codec” will struggle to achieve. Low latency and more reliable transmission should be easy to appreciate, while improvements in codecs (which have already been through more than three decades of refinement) and modest increases in bit rate are rarely easy to hear.

Unfortunately, most people have never heard a legitimate test of audio codecs. For the test to be legitimate, the listener can’t know which codec he or she is hearing; the test must be at levels matched to within plus/minus 0.1dB; and the reproduction chain (i.e., the amplifier, speakers/headphones, etc.) must be the same for all codecs. Such tests are complicated to put together, but there’s one on my website that you can easily try. Just plug a set of ordinary passive headphones or earphones into your computer or phone and have at it. The computer or phone doesn’t have to have aptX, and it doesn’t even have to have Bluetooth.

Most of the people who’ve tried the test on my site tell me that it’s pretty easy to hear the difference between an original, uncompressed file and a file that’s been transmitted through Bluetooth, but few report having a clear preference for any of the different codecs used for Bluetooth. (That’s for the tests with SBC and standard aptX; I just added aptX HD so I haven’t gotten much feedback on that yet -- but I’d greatly appreciate it if you take the latest version of the test and share your results with me.)

We’ll have to wait till 2019 to get a real hands-on evaluation of aptX Adaptive. “There are some early engagements underway with several of the licensees,” Havell said. “We certainly expect to see products next year. There may even be some announcements at CES.” Of course, as with other Bluetooth codecs, aptX Adaptive will work only if both the source device (i.e., your phone, tablet, or computer) and the sink device (i.e., Bluetooth headphones or speakers) incorporate the technology. Otherwise, the two devices will switch to a codec that they both support, such as a different variant of aptX, or the AAC format supported by Apple iOS devices, or Bluetooth SBC.

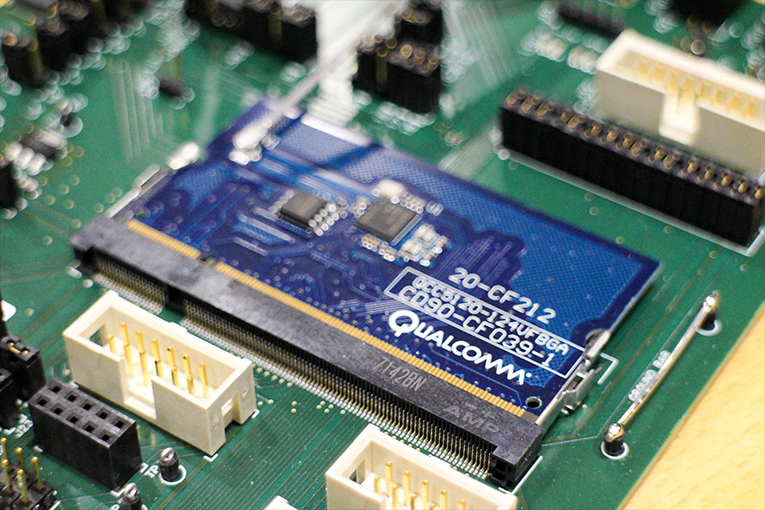

Unfortunately, there probably won’t be aptX Adaptive firmware updates available for existing aptX-equipped products. “Updating existing products probably won’t be possible, because the codec uses a bit more processing power to shrink and continuously adapt the bit rate,” Havell said. “The new QCC5100 series [a new system-on-a-chip for Bluetooth headphones] has the DSP horsepower to support this.”

Even though almost all of my headphone use is for music listening, I’m looking forward to trying aptX Adaptive. If it can keep the Bluetooth signal from sputtering out when I put my phone in my pants pocket, I’ll consider that the most welcome advance in wireless technology in years.

. . . Brent Butterworth