Thanks to recent research, we now understand a lot about headphones. But there’s one part of the headphone puzzle that I haven’t understood at all, and until a few weeks ago, neither did anyone else I’d talked with. It’s a phenomenon I call “eardrum suck,” and it occurs with some noise-canceling headphones. When you put the headphones on and activate the noise-canceling function, it can cause a feeling like riding a high-speed elevator, where you’re whisked abruptly into a region of lower atmospheric pressure, and the higher-pressure air inside your ear pushes your eardrums out slightly. For many, including me, it’s an effect so uncomfortable it can cause us to leave our expensive noise-canceling headphones in a drawer, unused.

Until recently, the models most notorious for eardrum suck have been Bose over-ear noise-canceling headphones, such as the QC25s and QC35 IIs. Yet as anyone who’s taken a commercial airline flight in the last decade can attest, these models are immensely popular. Clearly, some people either don’t experience eardrum suck, or do experience it but aren’t bothered by it.

Also, I and others noticed that the problem doesn’t seem to occur with Bose’s QC20 and QC30 noise-canceling earphones, even though those models deliver noise-canceling performance comparable to the over-ear models.

The question arose again when Sony came out late last year with the WH-1000XM3s, the first headphones I’ve found that deliver measurably better noise canceling than the Bose equivalents. Against my hopes but confirming my fears, I and some of my colleagues noticed that the WH-1000XM3s’ eardrum suck seemed about as bad as the Bose QC35 IIs’.

I’d asked some of the best minds in the headphone business to explain what’s going on, but no one was able to give me a plausible answer; “We’ve been wondering about that, too,” was the most common response. I searched around on the Internet, but none of the purported explanations (such as the idea that the noise canceling allows you to hear the blood pumping through your ears) survived more than a few moments of scrutiny.

Last fall, I even built a test rig to measure the pressure inside a headphone. But while it was sensitive enough to pick up the minuscule pressure difference caused by lightly tapping a finger on the earcup, it didn’t detect any pressure difference when I switched the noise canceling on and off. The more I thought about it, the more I realized this shouldn’t have surprised me. If there were added pressure in the headphones, the pressure would be relieved merely by shifting the earpads slightly to let the pressure leak out.

Then I remembered I’d once met an audio engineer whose previous work in headphone noise canceling has resulted in several patents. I thought that because he doesn’t work directly for a headphone manufacturer, he might be willing to shed some light. Through a mutual acquaintance, I was able to connect with him over Skype. At his request, I won’t share his name, but his comments gave me the first plausible answer I’ve found on this topic.

Before we continue, it’s important to understand how noise-canceling headphones work. In all noise-canceling headphones, there’s a microphone inside the earcup, near your ear, that picks up the sound inside the earcup, which is a mixture of the music coming from the driver plus environmental noise leaking in through the headphones. The headphones route the sound from the microphone back into the headphones’ internal circuitry, out of phase with the music signal. This cancels out most of the music signal and leaves the noise. The resulting noise signal -- which is out of phase with the environmental noise coming in through the headphones -- is then routed back into the amplifier’s input. Because the driver then reproduces this noise that’s out of phase with the environmental noise, it cancels the environmental noise.

This is called feedback noise canceling. More advanced noise-canceling headphones, such as the Bose QC35 IIs and Sony WH-1000XM3s, add feed-forward noise-canceling, which uses a microphone (or two) on the outer shell of the headphones to pick up the environmental noise. The noise signal from the microphones is inverted in phase and sent into the driver, so the noise is canceled. Combining the feedback and feed-forward systems results in the maximum possible noise canceling available with today’s technology.

At last, the answer

According to the engineer, eardrum suck, while it feels like a quick change in pressure, is psychosomatic. “There’s no actual pressure change. It’s caused by a disruption in the balance of sound you’re used to hearing,” he explained. “People sometimes report the same effect when they go into anechoic chambers, which absorb high frequencies but allow low frequencies to come through. With noise-canceling headphones, it’s the opposite -- you’re canceling the bass but not the high frequencies -- but it can have the same effect.”

“With noise-canceling headphones,” he continued, “cancelation is dependent on waveform matching [i.e., the cancelation signal waveform must be 180 degrees out of phase with the noise]. That’s no problem in the bass because the waveforms are so long. But you have to bring the cancelation back to zero at higher frequencies, because the wavelengths are shorter and the headphones will start to squeal.”

What that means is that at higher frequencies with short wavelengths, the canceling signal can start to reinforce certain frequencies rather than cancel them. The “squeal” he refers to is feedback. Technically, it’s much like the feedback you get when you put a microphone in front of a P.A. speaker. The sound waves from the speaker excite the microphone diaphragm, which sends that signal back into the P.A., which is amplified and again picked up by the microphone, and you get a self-reinforcing signal loop -- and a squeal that continues until you pull the microphone away from the speaker.

To eliminate the possibility of squeal, noise-canceling headphones use a filter that limits the noise-canceling effect to low frequencies. It’s this filter that introduces the “disruption in the balance of sound you’re used to hearing” he spoke of previously.

“I’ve played with the noise canceling a lot,” he said. “I’ve changed the compensation on the fly, while I was wearing the headphones, and could hear what was going on. I could start with a modicum of cancelation, then increase the filter slope to give the maximum cancelation, and I could feel the pressure effect increasing. If the transition is very steep -- if you try to get as much cancelation in the lows as possible, then have to bring it abruptly back to zero by using a steeper filter slope -- that mode gives you the most pressure effect.”

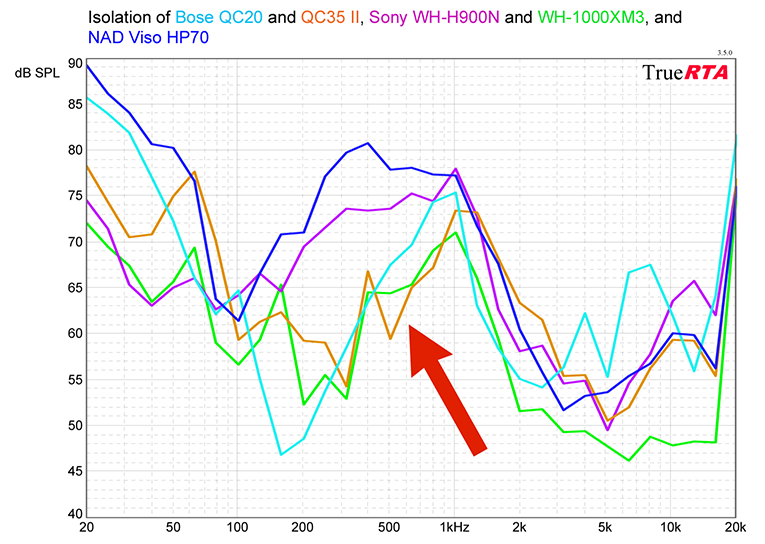

You can see this in measurements of noise isolation versus frequency, which I include in all SoundStage! Solo headphone reviews. Below is a chart that shows the isolation provided by several noise-canceling headphones. The red arrow shows the filter slope the engineer is talking about. You can see that with the Bose QC35 IIs and the Sony WH-1000XM3s, the cancelation in the bass is very strong, and there’s a more abrupt transition from maximum canceling at about 100 to 300Hz, to zero canceling at 1kHz. (The isolation you see at 1kHz and higher frequencies results from the passive isolation provided by the physical structure of the headphones, not from the noise-canceling circuitry.) The Sony WH-H900Ns, which in my experience produce just a slight amount of eardrum suck, have a gentler filter slope. The NAD Viso HP70s, which for me produce no eardrum suck, focus a relatively modest amount of noise canceling within a narrow band.

Note that the Bose QC20 earphones have a slope just about as steep as the QC35 IIs and WH-1000XM3s, but in my experience, the QC20s don’t produce eardrum suck. Why? I asked the engineer.

“I’ve not had the experience of many in-ears that do cancel well; an awful lot of them do not,” he replied. “It may be the fact that they give a good amount of passive isolation as well” -- which would make the difference in noise between the low and high frequencies less pronounced. In this case, the theory doesn’t correlate as well with the measurements, because with the Bose QC20s, the isolation above 1kHz actually isn’t as good as it is with the over-ear models because the QC20s’ StayHear tips don’t seal as securely as many other earphone tips do. Still, it appears that the acoustical effects of plugging the ear canal eliminate the eardrum suck effect, for whatever reason.

The bottom line is, the eardrum suck phenomenon isn’t directly caused by highly effective noise canceling. It’s a side effect caused by the filter required to achieve highly effective noise canceling without encountering feedback problems. So it appears we may always have this tradeoff -- the headphones with the best noise canceling will produce the strongest eardrum suck effect. But as the engineer pointed out, a solution to the problem is possible, although it might not be an engineering solution.

“I became inured to it after working on these headphones for a while, so maybe it’s like an addiction -- maybe you can train yourself out of it,” he concluded.

Postscript: Since this article was published, I’ve noticed that some people are taking it as a criticism of noise-canceling headphones. It’s anything but. Only a few noise-canceling headphones exhibit eardrum suck, and many models (such as the Sony WH-H900Ns) deliver a useful amount of noise canceling without producing eardrum suck. And as you can see if you read my article “How Much Noise Do Your Headphones Really Block?” here on SoundStage! Solo, the passive isolation provided by headphones and earphones does almost nothing to reduce the annoying drone of jet engines. So for frequent flyers, noise-canceling headphones are by far the best choice for listening on the go.

. . . Brent Butterworth