It’s hard for me to believe it’s been seven years since researchers from Harman International presented the landmark paper “The Relationship between Perception and Measurement of Headphone Sound Quality” at the 2012 Audio Engineering Society Convention in San Francisco -- the first paper in which the company presented what became known as the “Harman curve,” the target frequency response that average listeners would like best. When I first read that paper, I assumed it would quickly revolutionize the headphone business. As a headphone reviewer, I knew that the various headphones and earphones then on the market often exhibited wildly different sounds -- even among different models in a company’s line -- which indicated that knowledge was lacking or simply being ignored.

Yet we didn’t see a surge in headphones claiming to use the Harman curve -- not even from Harman companies AKG, JBL, and Harman Kardon, although other manufacturers had quietly confided to me that they were basing their designs on the Harman curve. In fact, the first set of passive headphones I’ve received from a Harman company using the Harman curve came across my desk only last month: the AKG K371s -- and the only way I knew that they were voiced within 1dB of the Harman curve was by reading a Facebook post from Harman senior fellow Sean Olive.

It looks, though, like the dam is finally bursting. In a presentation last month to the Los Angeles chapter of the AES, Olive highlighted several other headphones and earphones designed along the lines of the Harman curve (although not, as best I can tell, marketed as such). The earphones include Samsung Galaxy Buds; JBL Live 200s, Live 500s, Live 650s, and Reflect Flows; and AKG N5005s. Headphones, for now, seem to include only the AKG N700 NCs, K371s, and K361s, but we can expect more. As Olive told me later in an e-mail, “Basically all new AKG headphones are designed to Harman target, and for the past year JBL has followed it but with 2dB extra bass below 125Hz.”

Olive’s presentation detailed Harman’s ambitious research into headphones, which has since 2012 resulted in 19 papers, one patent (and three more pending), and a one-click routine for the SoundCheck audio measurement suite that uses the Harman curve to predict listener preference. The effort started with the realization that, as Olive put it, “There were standards for diffuse-field and free-field headphone response, but no one was following them so there must have been something wrong.

“At the time, our marketing department was telling us that we should duplicate the response of Beats headphones, because those were the best sellers,” he continued. But Harman’s researchers had already evaluated those headphones in blind tests, and they found them to be unpopular among their listeners. “So we told them they should duplicate Beats’ marketing instead,” he said.

The researchers’ idea was that if headphone designers knew what measured response best suited the largest number of listeners, the designers could then tailor their products’ frequency responses to that target. This would be more efficient than “shooting in the dark” by building headphones, putting them through listening tests (which, if you want them to be blind, are much more complicated with headphones than they are with speakers), then repeating the process until most of the listeners are pleased.

Harman’s first effort involved a blind test of six over-ear headphones, followed by measurements of those response curves to see which response pleased the most listeners. Subsequent projects solicited the judgment of hundreds of listeners around the world and measurements of hundreds of different headphones.

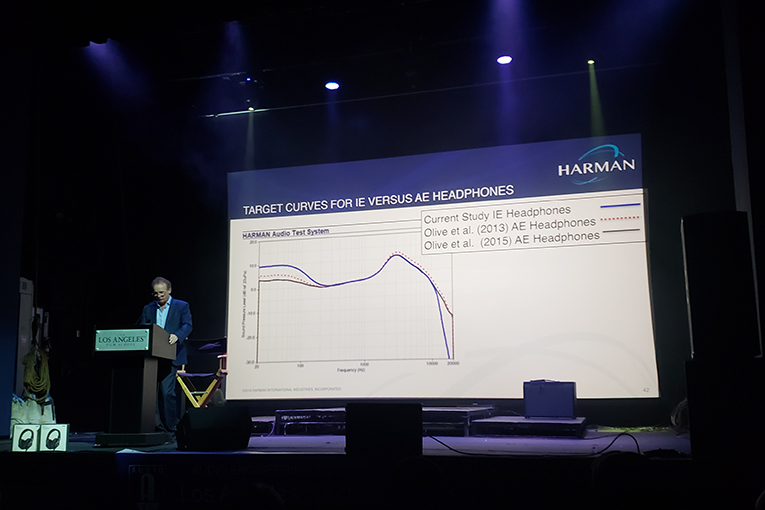

The results of all that effort were Harman curves for earphones and over-ear headphones. But as Olive suggested in his above comment about JBL headphones, it’s not a “one size fits all” target. His presentation identified three potential groups to which manufacturers can target their headphones.

“Harman curve Lovers”: This group, which constitutes 64% of listeners, includes mostly a broad spectrum of people, although they’re generally under age 50. They prefer headphones tuned close to the Harman curve.

“More Bass Is Better”: This next group, which makes up 15% of listeners, prefers headphones with 3 to 6dB more bass than Harman curve below 300Hz, and 1dB more output above 1kHz. This group is predominantly male and younger -- the listeners JBL is targeting with its headphones.

“Less Bass Is Better”: This group, 21% of listeners, prefers 2 to 3dB less bass than the Harman curve and 1dB more output above 1kHz. This group is disproportionately female and older than 50.

According to Olive, his group still has some more research into headphones to do, but they’re starting to wrap it up and anticipate moving on to new projects. We don’t yet have enough information to know if the Harman curve will result in greater sales, millions more happy listeners, and better standardization of headphone evaluation. I’ve learned from listening to several headphones and earphones that come close to the Harman curve that it is, at the very least, an excellent baseline for performance. Headphones and earphones may, for various reasons, deviate to some extent from the Harman curve. But if their measured response is far from the Harman targets, listeners and reviewers should at least question why, and the manufacturer should be able to respond with a plausible rationale based on research and testing.

I expect we’ll encounter manufacturers and reviewers who simply claim, “I listened to some Harman curve headphones and I don’t think they sound very good.” Audio enthusiasts will then have to decide whether they trust the conclusion of a single person, determined through casual, sighted testing, or the conclusion of years’ worth of research conducted with hundreds of listeners in carefully controlled blind tests. I know which way I’ll go.

. . . Brent Butterworth