Two recent experiences have reminded me of an old and very important lesson about audio I and many thousands of other audio enthusiasts learned decades ago. But the lesson seems mostly forgotten. The first experience was a couple of “run-ins” with other audio writers -- one directly, on Facebook, and the other indirectly, through an editor friend of mine. The second was recording and mixing I’ve done for what will soon be my first jazz album: a collaboration with saxophonist Ron Cyger under the name Take 2.

Both of the writers in question have at least 20 years of reviewing experience. Both would, I’m sure, tell you that their ears are their ultimate reference. Both of them rely on the most basic, “single presentation” method of product evaluation: they replace a component in their reference system with the product under test, and they describe the sonic differences they hear. They claim to “know what to listen for.” They believe their conclusions from these evaluations to be correct, comprehensive, and reliably predictive of other audio enthusiasts’ reactions to the product in question.

The problem, as I was reminded during my recording and mixing sessions, is that whether one person likes the sound of an audio product is not a reliable indicator of the performance of the product, because that person has only a foggy idea of what the music they’re listening to is supposed to sound like. Nor is their opinion a dependable predictor of others’ opinions.

As I’ve been recording and mixing, I’ve been struck by how many routine decisions I make that have huge impacts on the sound yet are made entirely according to my personal taste, with at best a vague acoustical memory of an instrument as a reference. For this project, I usually lay down the rhythm tracks on bass, guitar, and/or tenor ukulele, then send them to Ron so he can overdub the sax and flute parts. As you can see in the accompanying photo, I sometimes do a lot of EQ on his alto sax tracks. He uses good-quality, large-diaphragm condenser microphones, and presumably he thinks the recordings are a reasonable representation of what he sounds like. To me, though, some of them sound way too bright, so in those cases I boost the low frequencies, notch out the upper midrange around 1.6kHz, and pull the treble down about 2dB.

Of course, Ron’s reference for what he should sound like is his own live playing, which his ears always encounter from their position an inch or two above the saxophone mouthpiece. My reference is also Ron’s live playing -- which I usually hear from six feet behind him, with his saxophone pointed toward the audience, reverberating through the space, and clouded by the competing sounds of bass and keyboard amps booming at my feet and a drummer spang-a-langing away on a ride cymbal an arm’s length away from me.

Obviously, neither of us can be sure what’s the most accurate portrayal of Ron’s alto sound; all we know is what we like. So how could someone listening to our future album be sure what it’s supposed to sound like?

You might think that I, as a double bass player, would know how a double bass sounds. But not only do the basses themselves sound different; the strings (which could be steel, synthetic fiber, natural gut, or a combination of any of these) can sound even more different, and the bassist’s technique can play a still-larger role in the character of the sound.

And then, of course, there’s the choice of microphone to record with. I, like many double bass players, prefer the Electro-Voice RE20 -- a large-diaphragm dynamic microphone designed for radio announcers, not instruments -- but I know bass players who’ve done excellent recordings with large-diaphragm condenser microphones such as the AKG C414, small-diaphragm dynamics such as the Shure Beta 56A, and many other microphones. All of these microphones sound different, and recordings from them are always EQ’d to the taste of the recording engineer, the producer, or the bass player -- and of course, they make those EQ decisions using monitor speakers or headphones that have a different frequency response from the ones you use.

Shure Beta 56A, Electro-Voice RE20, and MXL 990

Shure Beta 56A, Electro-Voice RE20, and MXL 990

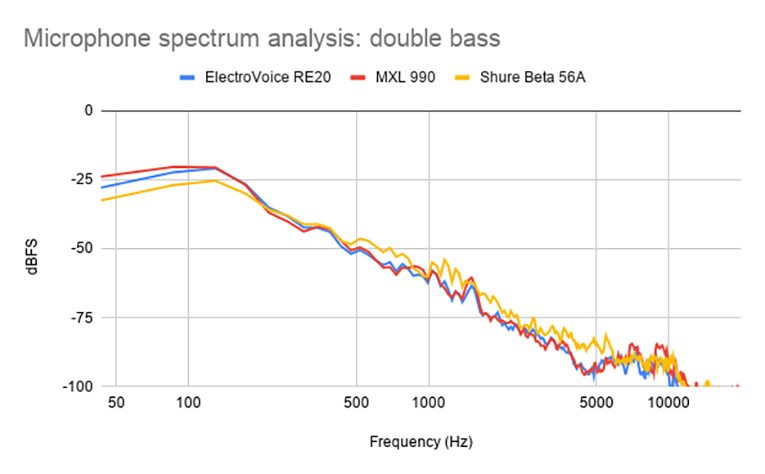

To illustrate this, I simultaneously recorded a pizzicato passage on my bass using three different microphones: the RE20 and Beta 56A, plus an MXL 990 large-diaphragm condenser microphone. I placed them close together, matched their levels at 400Hz using a sine wave played from a Bluetooth speaker, and recorded all three at the same time. I then imported the files into Room EQ Wizard and ran a spectrum analysis on them.

You can see in the accompanying chart below that the Electro-Voice RE20 is similar to the MXL 990, but with a few dB less response below 100Hz, which to my ears gave it a somewhat less boomy sound. But the Shure Beta 56A -- which I found out about from Lynn Seaton, one of the world’s best-known jazz bass teachers, who uses it for his recordings -- has a much more trebly tonal balance, with more apparent treble detail but weak low-bass response. You could EQ these microphones to sound more similar, but it’s unlikely you could get them to sound the same.

The bottom line is that there are so many variables in any recording that it’s difficult for even the most experienced listener to be sure what’s right. Only if there’s a glaring flaw -- if, for example, an audiophile-oriented headphone is bass-deficient (or treble-abundant) enough to mask the fundamental tones of the double bass, or if a bass-heavy mass-market headphone takes all the breathiness and upper harmonics out of a flute recording -- can we be confident in our assessment that the headphones are doing something wrong. After all, those sonic characteristics are part of the reason that musicians and producers choose those instruments in the first place.

This lesson first hit me about 30 years ago when I bought the original Stereophile Test CD, which featured the magazine’s founder, J. Gordon Holt, reading his essay “Why Hi-Fi Experts Disagree.” Slyly, Holt, and the magazine’s then-editor, John Atkinson, recorded the essay employing many different commonly used, well-regarded studio microphones for the recording, changing the microphone every few sentences. The differences in the tone of Holt’s voice and in the level and character of the noise floor every time the microphone is changed are in most cases easy to hear, especially through headphones.

As the recording demonstrates, if every acoustical instrument or voice you hear through your system was captured by a microphone, and you don’t know what that microphone sounds like -- or what that instrument or voice sounds like, or how the venue affects the sound -- how can you be certain what the recording is supposed to sound like?

My intent here is not to suggest that we should ignore what our ears tell us when we listen to music and rely strictly on measurements to evaluate audio products. It’s merely to show the limitations of what music recordings can tell us about the performance of an audio product -- and to illustrate the folly of believing oneself so skilled at listening that one’s opinion of that product is definitive and universal. Anyone who’s conducted a few blind tests can tell you of the chagrin they’ve felt when interviewing test participants and finding that two experienced listeners with healthy hearing can have conflicting opinions of the same product.

But while some of my colleagues in the audio-measurement community may not agree, I feel that we need to hear about that subjective experience to understand audio, even if the subject’s experience isn’t predictive of ours. I’d guess that most audiophiles got into the hobby after witnessing the passion of other audiophiles -- something that’s unlikely to spring from a session at the test bench. The facts of audio come mostly from measurements, but the story of audio can be inspired only by listening.

. . . Brent Butterworth