There’s much to love about YouTube (Rick Beato, Rahsaan Roland Kirk playing “I Say a Little Prayer”), but it’s coming at a price: the dumbing down of the audio industry. I got some inkling of this future in 1990, the first year of my audio career, when an acquaintance asked me, “How are those Bose speakers? I heard them on a TV commercial, and they sounded pretty good.” He was in the oil biz, not the audio biz, so I didn’t blame him for failing to grasp that he was hearing not a Bose system, but recorded music played through his TV speakers. Yet thanks to the Internet’s negligible barriers to entry, people who claim to be audio experts are now making the same mistake he did.

I’ve noticed an increasing desire among manufacturers, retailers, and reviewers to demo audio products over the Internet—streaming some representation of the sound of a headphone, a speaker, or even an amplifier through a webpage, YouTube, etc., with the idea that you can listen to it from home and judge the sound quality for yourself. In an era when it’s nearly impossible to get a demo in person, the appeal of this method is obvious. However, the people who do it rarely consider the problems involved.

A good example is a YouTube video I saw the other day, where a reviewer described a high-end audio system and then said, “Let’s give it a listen, shall we?”—and played a recording through the system. Any audio pundit worthy of respect would know that you’re not hearing just that featured system—you’re also hearing the acoustics of the room it’s in, plus the response of whatever unidentified microphone was used for the recording, plus the artifacts of the audio codec used to stream the video, plus the characteristics of whatever audio gear and room you’re using to listen to the YouTube video. It tells you nothing about the performance of the audio gear featured in the video. It’s as absurd as trying to judge the quality of a wine by first mixing it with two or three other wines before you drink it.

In the desire to alert readers to the inherent flaws of these demos—and in the hope that they might someday be conducted with more thought and care—I thought I’d use this column to highlight the only laudable online demo effort I’ve seen, and explain where other attempts went wrong.

The one good effort

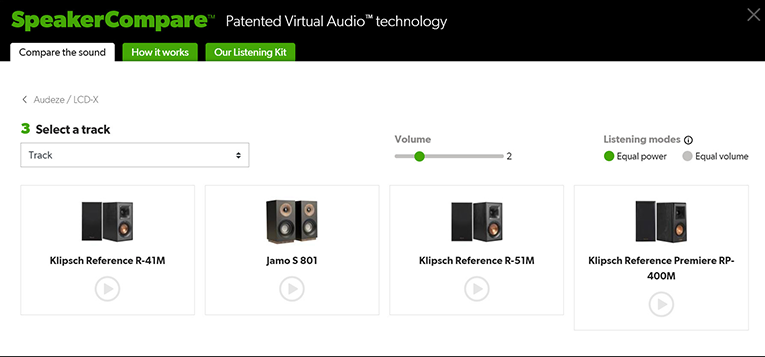

By far, the most serious attempt I’ve seen at doing audio demos on the Internet is the SpeakerCompare feature on the Crutchfield.com website, which lets you compare speakers online through headphones. SpeakerCompare attempts to eliminate any sonic changes your headphones make to the sound, using compensation curves based on Crutchfield’s own measurements of numerous headphones. Before being streamed through the website, the music selections are processed using Crutchfield’s measurements of the speakers, which were made in an anechoic chamber. Further processing simulates the effect that a typical room will have on the speakers’ sounds.

The system is wonderfully simple to use: select your headphones, choose a music track from one of several genres, and then click the onscreen Play button under the speaker you want to hear. It’s easy to switch between speakers and listen at whatever level is comfortable for you.

This effort couldn’t have been more earnest. I’d guess it cost Crutchfield between half a million and a million dollars, including consultation by a couple of PhDs. Even so, I’d rank it as only modestly successful.

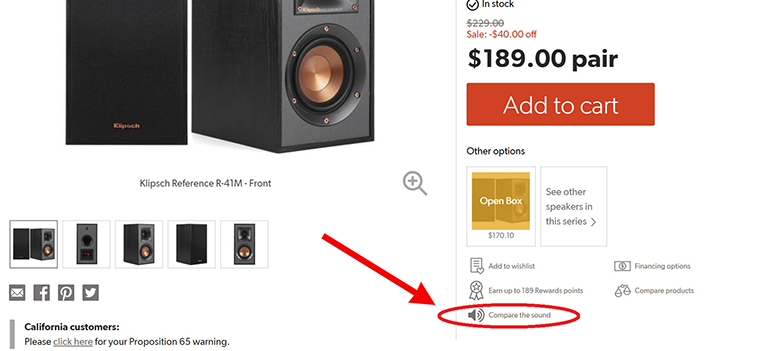

I happen to have Klipsch Reference R-51Ms, which are among the speakers included in SpeakerCompare, so I was able to compare the sound of the actual speakers in my listening room (playing the same tunes, but from Spotify) to the sound of the speakers simulated through Audeze LCD-X headphones. I’d say the simulation got the midrange about right—in both presentations, it had that “little bit bright” sound characteristic of Klipsches in this price range. But the bass was considerably elevated in the simulation, which made the treble sound subjectively softer, so I wasn’t getting an accurate idea of what the speaker sounded like.

Comparing the simulated R-51M to a simulation of the Jamo S 801, I could tell that the Jamo sounded a little bassier and a little softer—no surprise, as it has a conventional dome tweeter versus the R-51M’s horn-loaded tweeter. But because of the overall bass-heavy coloration of both presentations, I couldn’t gauge which speaker I’d like best. My results were almost the same when I switched to the AKG N60 NC headphones, which are included as a listening option in SpeakerCompare. The differences between the simulation and my live, in-room listening should come as no surprise, as it’s unlikely the acoustics of my room match the profile Crutchfield used to create the simulation. Perhaps I’d have gotten better results had I popped $25 to rent the SpeakerCompare Listening Kit, which includes a set of Sennheiser headphones that I assume were chosen to give optimum results.

Despite the considerable effort Crutchfield put into developing SpeakerCompare, the company doesn’t claim it’s a substitute for a live demo, and Crutchfield encourages customers to make their final speaker choice only after a free in-home trial. Sadly, none of the other people I’ve seen offering online audio demos are so dedicated . . . or anywhere near as wise.

The many bad ones

On the flip side, there’s an unfortunate trend in YouTube reviews to simply record the sound coming from headphones or speakers in some convenient and inexpensive manner, and stream the result as a representation of that product’s performance, with little or no regard for what changes the sound might go through between the product’s transducers and the listener’s ears.

In one example I recently saw, a reviewer on YouTube was attempting to demonstrate the sonic characteristics of headphones by playing music through them, recording the result through a miniDSP EARS headphone measurement rig, and streaming that out to his viewers. Presumably, the viewers would listen to the result on headphones, although I can’t recall whether the reviewer made any particular suggestions in this area. So they could be listening on a $50,000 stereo system, through the speaker built into their phone, or anything in between.

To understand the problem here, remember that the actual experience in a real-world evaluation of a set of headphones has two fundamental components:

- The characteristics of the headphones under test

- The acoustical and psychoacoustical characteristics of your ears and brain

When you’re listening to the video described above, you’re hearing not just two components but four fundamental components:

- The characteristics of the headphones under test

- The characteristics of the ear simulator used for the recording (in this case, the miniDSP EARS)

- The characteristics of the headphones (or speakers) and electronics used for monitoring

- The acoustical and psychoacoustical characteristics of your ears and brain

Obviously, what you’re hearing from the audio stream, through your headphones or speakers, will be very different from what you hear when you listen directly to the headphones being demonstrated. You may be able to hear a difference between two products demonstrated in this fashion, but you won’t be able to put it in perspective. How can you tell if a headphone with a 6dB peak at 3kHz sounds better than a headphone with an 8dB peak at 2kHz if you’re listening through an artificial ear that doesn’t conform to any industry standards, and then through your headphones, which contribute their own peaks and dips?

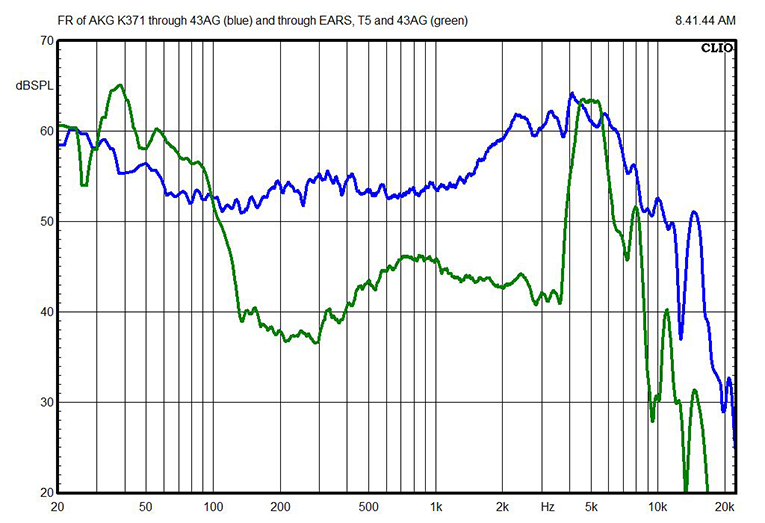

To illustrate how much the sound of headphones can change in an online demo, I measured the frequency response of a set of AKG K371 headphones mounted on a GRAS Model 43AG ear/cheek simulator, using white noise. Then I mounted the K371s on a miniDSP EARS, ran that sound into a computer, and monitored it through Beyerdynamic T5 (3rd generation) headphones, which I then mounted on the 43AG.

You can see the result on the chart above. It’s a huge difference, and it was unpleasant to listen to—yet this is actually better than what a typical listener will experience, because the audio hasn’t gone through one of the various audio-compression codecs YouTube uses, and the T5s are a better monitoring system than probably 99% of YouTube users will have.

I’ve often seen people who do online audio demos (and who measure using the miniDSP EARS) admitting their system isn’t perfect but saying, “I think it’s pretty close.” Yet this is just their gut feeling; I’ve never seen any of them present any sort of methodology they used to come to their “pretty close” judgment, and few, if any, have the equipment or the expertise to create such a methodology. Their gut feeling that their result is “pretty close”—without, of course, having the slightest clue what equipment their viewers are using to listen—may satisfy some YouTube viewers, but anyone with a grasp of audio engineering will reflexively roll their eyes.

I think it’s possible to do halfway decent online audio demos, at least of headphones. One way you might actually get “pretty close” is to mount a popular set of headphones, such as Sony’s MDR-7506, on the miniDSP EARS and measure the combined transfer function—i.e., the total change made in the frequency response by the EARS and the Sonys. Use an equalizer or an audio processing plug-in to create an inverted version of that transfer function, and use that curve to process the sound on the video. Now put whatever headphones you're testing on the EARS, and stream that audio, processed with the equalizer. When the listener puts on the MDR-7506 headphones (which many headphone enthusiasts and audio pros already own, and which typically cost only about $99), in theory, at least, they’ll be hearing the frequency response of the headphones under test, minus the sonic effects of the EARS and the Sonys. Of course, it would work correctly only with the MDR-7506 headphones, and maybe tolerably well for a few headphones with a similar response. Ideally, you’d offer listening options for several popular headphones, as Crutchfield does, although that would be practical only on a dedicated website—on YouTube, you’d have to offer a separate video for each headphone model.

I did something similar to this for the demo videos accompanying my article “How Much Noise Do Your Headphones Really Block?” It was complicated, but it worked fairly well—although I was demoing noise levels, not the subtleties of an audio product’s performance, so the frequency response of my viewers’ audio systems didn’t matter much.

I hope that if reviewers and retailers who do online demos consider how much effort and expense Crutchfield put into SpeakerCompare, they’ll realize how amateurish it is for someone to just hook up a microphone or a cheap headphone measurement rig and hope for the best. And I hope they’ll invest some time, money, and creative (but informed) thinking in making their online demos more useful. But in a subculture where an unsupported assertion that something’s “pretty close” satisfies enough viewers for the presenter to turn a profit, I’m not optimistic that this will happen.

. . . Brent Butterworth