When someone on Facebook recently commented, “Compressed audio sounds horrific, and even uncompressed 16/44.1 isn’t great,” I felt terrible. I knew he came to these conclusions not through any sort of careful, unbiased testing, but because the audio industry—manufacturers, press, dealers—has told him he shouldn’t like compressed audio, and that 16-bit/44.1kHz audio is, after decades of enthusiastic acceptance by billions of users, now unacceptable.

The audio industry has convinced this poor guy that he shouldn’t enjoy music unless it’s on whatever formats have recently won the favor of audio writers—and reproduced with the maximum resolution offered by streaming services or the newest DACs.

Meanwhile, billions of people are getting great joy from music using all sorts of technologies: compressed digital streams, radio broadcasts, smartphones, computers, cheap earphones, tiny speakers built into laptops, etc. Without a moment’s reflection, they know music works—its ability to convey the artist’s emotion, creativity, and intellect is independent of the reproduction chain.

Those who’ve read my columns for a while may have noticed I’ve become less tolerant of the notion that using certain technologies, spending a fortune on gear, or seeking out in-vogue audio brands is somehow “critical” to music reproduction. Blame the double bass.

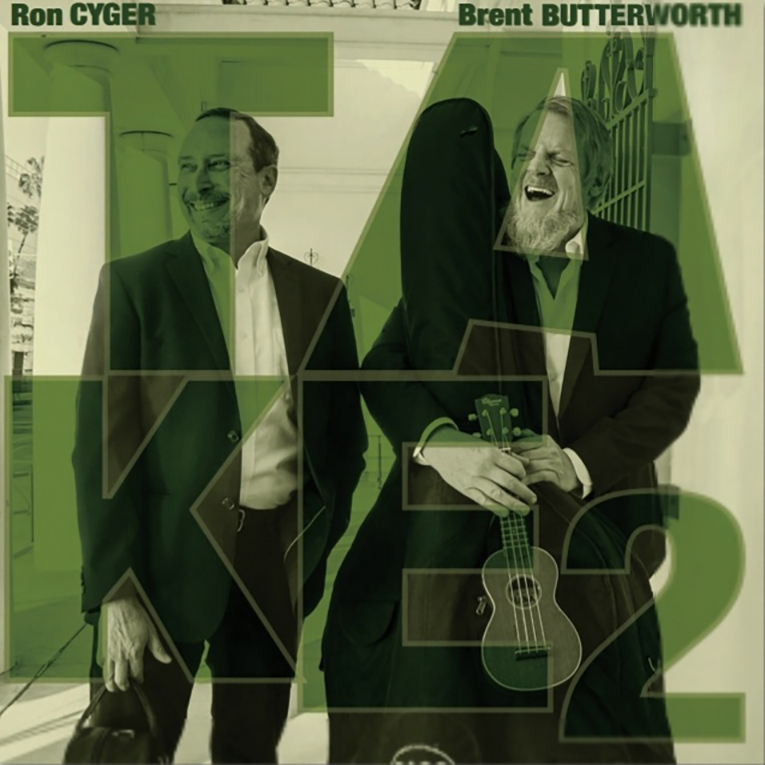

I’ve played music for 40-plus years, but I got serious about it only a few years ago, when I started playing double bass—the first instrument I truly fell in love with, and one that’s pretty easy to get work on. Since then, I’ve played perhaps 150 jazz gigs, and I just released my first real album: Take2, a batch of mostly original tunes I put together with saxophonist Ron Cyger. Through my efforts, I’ve come to a new understanding about what’s really important in music—and which parts of the audiophile ecosystem have nothing whatsoever to do with music.

Listen to musicians talking, and you’ll hear discussions about melody, harmony, and rhythm—not about inner detail, microdynamics, texture, or any of the other things stressed on audio forums and touted in audio product advertising. Whether such jargon describes real phenomena or exists merely to glamorize and mystify what should be a simple and rewarding activity, the fact is that at all my gigs and jam sessions, and in all the dozens of recording studios I’ve visited, I’ve never once heard these terms used. Musicians don’t worry about inner detail—they’re concerned with intonation, timing, and tone, and only the very worst audio components are incapable of conveying those elements.

This may be why so few musicians bother with fancy audio systems. Of the countless musicians I know, one might qualify as an audiophile—if only because he took the trouble to check out head-fi.org before he bought his most recent set of headphones, the $220 Massdrop x Sennheiser HD 6XX.

Around 1990, I was drawn to the passionate quest for better sound expressed in magazines like Hi-Fi Heretic and the old digest-sized Stereophile. Back then, no one was really sure what good sound was. Speaker designs often contained all sorts of drivers pointed in bizarre directions, and hardly any headphones had sound you could call natural. At about that same time, though, controlled listening tests started to show us what matters in music reproduction (frequency response of speakers and headphones, mostly) and what doesn’t. Soon, it became simple and affordable to put together a stereo system with sound that’s probably as realistic as a set of transducers can deliver—and easily able to reveal, say, the decades of work that Joe Henderson put into his sound, or the thought that George Martin put into his EQ and reverb decisions.

But much of the audio industry has moved its focus well outside the now-simple task of reproducing music faithfully. Sure, we can get straightforward products like the AKG K371 headphones and the Triangle Borea BR03 speakers that are designed purely for the purpose of realistic music reproduction. This is the kind of audio gear I’ve found my musician friends tend to appreciate, mainly because these products tell them what they sound like to the rest of the world.

Audio shows rarely focus on such products now. In my opinion, the focus at shows, and in the high-end audio industry in general, has shifted away from the real-world demands of music reproduction and more toward consumerism. Products that the industry got right decades ago—DACs, amplifiers, cables, etc.—are gussied up to meet higher price points by adding ornamentation or pumping up the resolution far beyond what any microphone could pick up, any human ear could detect, or any real-world listening environment could reveal. We see speakers increased to colossal sizes, with more drivers than you can count on one hand, and physical configurations that are less acoustically optimal than smaller, simpler designs. In some cases, it appears to me that the primary goal of these speaker designs is to give price-insensitive customers an opportunity to spend more—even though science shows us that the speakers that win in blind listening tests are usually well-engineered two-way or three-way designs.

Decades ago, Harry Pearson, founder of The Absolute Sound, conceived the notion of audiophiles as connoisseurs; he once described one of his critics as “someone who doesn’t know how to listen to music.” In Pearson’s heyday, when most speakers had extremely colored sound and few amps had the power to deliver realistic dynamics, he surely had a point. To this day, many audiophiles think of themselves as cultural elites who “know how to listen to music” and whose considerable and ongoing expenditures on hi-fi gear show how much they care about music.

But this attitude no longer reflects today’s realities. When we have audiophiles proclaiming that they refuse to listen to streaming services, or to wireless speakers, or to whatever technology or brand has fallen out of favor among audio’s chattering class even though controlled testing has shown it to be nearly or entirely transparent, they’re expressing consumerist sentiment, not artistic concerns. They’re getting their daily dopamine hit not so much from music, but from ogling their purchases and dissing others who haven’t spent as much money on audio gear as they have. They’ve forgotten how to listen to music.

They’re like the guy who insists that the drive up California’s Pacific Coast Highway can only be properly appreciated in a Ferrari, or that you really don’t know what Rombauer chardonnay tastes like until you drink it from a $200 Baccarat crystal wine glass. These sentiments don’t reflect a love of scenic views or wine—they reflect only ego-driven consumerism.

To these audiophiles, I say forget all the nonsense that the press, the internet, and the audio industry marketing machine has fed you, and just remember that music works. Sure, it’s fun and rewarding to pursue better music reproduction, but let’s not forget that music stirred the emotions of billions of people long before good audio systems existed. Music doesn’t need help from audio writers, internet commenters, or audio product designers who “know what music should sound like.” Those who let consumerism get in the way of enjoying one of humanity’s most satisfying creations are squandering their blessings. That’s what my bass tells me, anyway.

. . . Brent Butterworth