Through the last 44 years, David Chesky has revolutionized audiophile recording at least three times—once with his super-ambient stereo recordings, once with his unique approach to surround sound, and once with his Binaural+ technique targeted mostly at headphone users. Now he’s at it again with a whole new concept that owes nothing to his past work: Meta-Dimensional Sound, which delivers a recording in two different versions: one optimized for headphones, the other for speakers.

Listening to Meta-Dimensional Sound, you might not realize how radical a departure it is from Chesky’s past efforts—it’s still super-ambient, with clear and natural-sounding instrumental tones and, apparently, minimal post-processing. The difference is that on Chesky’s debut Meta-Dimensional Sound release, Graffiti Jazz, there are no acoustic instruments, and no microphones were used. It’s all done “in the box”—using digital audio workstation (DAW) software and MIDI controllers.

“Being shut in because of the COVID pandemic, I was bored,” Chesky told me. “So I opened up my DAW and started using electronic instruments and having a good time. I then started working with different ways to make the sound more ‘3D,’ and decided to see how big and spacious I could make things in the box.” (Asked which DAW he used, Chesky replied, “Oh, Pro Tools, Logic—I’ve got all kinds of stuff.”)

As anyone who’s listened to a few binaural recordings—or really, anyone who’s ever compared speakers with headphones—knows, the ambience in a recording sounds very different on speakers than it does on headphones. That’s why Chesky created two different mixes for each tune: one for speakers, one for headphones.

For example, on the tune “Graffiti Jazz No. 3,” which features samples of cymbals, double bass, muted trumpet, and distorted electric guitar against a Roland TR-808-style drum machine beat, the headphone mix, heard through headphones, has a more natural ambience, more like hearing musicians in a real performance space. But listen to the headphone mix over speakers, and the sounds take on an ethereal and somewhat disjointed aura.

Likewise, if you listen to the speaker mix over speakers, it has that huge, compellingly natural ambience audiophiles associate with Chesky Records. But if you listen to the speaker mix through headphones, the music sounds more “pan-potted,” with less ambience and each instrument more confined to a specific location in the soundstage.

Some mixes even have subtly different content—for example, the speaker track for “Graffiti Jazz No. 4” adds a bit of what seems like simulated street noise in the background, but on the headphone track, that noise is absent.

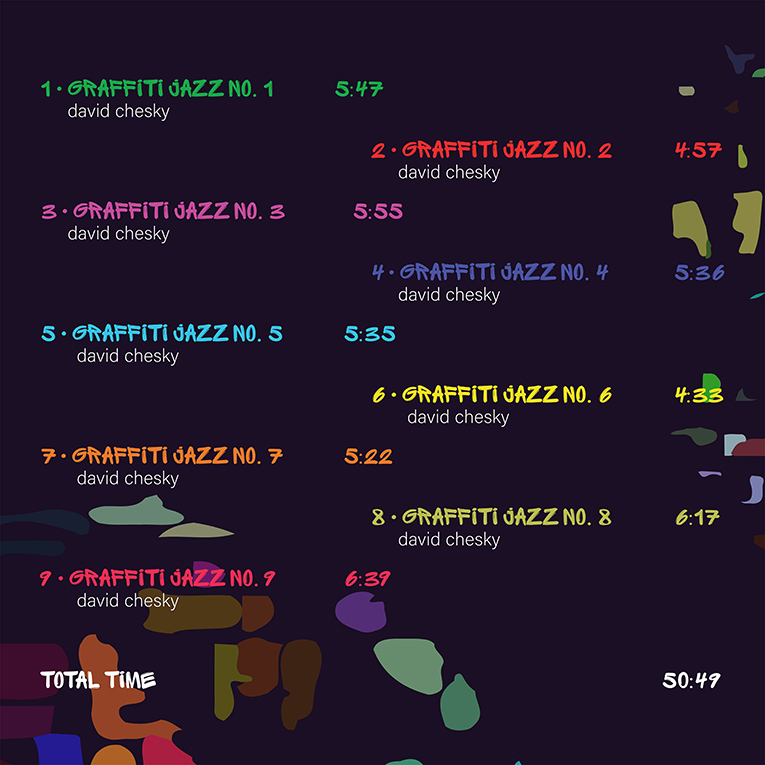

Each Meta-Dimensional Sound release will include both sets of tracks, either in higher-resolution PCM (24-bit/96kHz, in the case of Graffiti Jazz) or in DSD and 24/48 PCM. They’re available only as downloads through theaudiophilesociety.com, a new website created specifically for Meta-Dimensional Sound releases. The website offers a seven-tune sampler download that curious audiophiles can check out for free.

I asked Chesky if he used any stereo enhancement or surround-sound virtualizer plug-ins in his DAW to create the effect, but as I probably should have guessed, his methods were more organic—or at least as organic as you can get in a DAW. “I did it by mixing and how I add things together,” he explained. “I figured out all these formulas for how to get the ambience I wanted. It was all created by hand. It’s not the Chesky Records paradigm where we go into a church with two microphones and try to get that realistic ambience the natural way. It was like going from portraits into abstract expressionism.”

Being confined to his apartment with little access to acoustic instruments and no possibility of using ideal recording venues or top-notch New York supporting players, Chesky was inspired—and honestly, forced—to re-examine his compositional style. Anyone who’s heard his Jazz in the New Harmonic and Primal Scream albums will recognize the spare aesthetic; the music is free of chords played on, say, a piano or guitar, and relies on melody and basslines to imply harmonic content. With Graffiti Jazz, Chesky was able to tap into the DAW’s ability to access an infinite variety of samples that he could use to get the moods he wanted.

“I used beats and other sounds to create aural collages,” he said. “When you’ve got these sounds, why think about harmonic movement?

“Normally when I compose, I sit down with score paper, and the music is all in my head and I write it out. In this case, I didn’t have all the sounds in my head, and I had to try different options to find what I wanted. I got to use colors I could never use in an orchestra. I think this is more reflective of our world—we live in a digital world.”

Not every Meta-Dimensional Sound album will feature only samples—the release that followed Graffiti Jazz is Troublemaker, a blues power trio featuring Aayushi Karnik, a Juilliard-trained electric guitarist from Surat, India, accompanied by a bassist and a drummer. Following that will be releases by the Czech National Symphony Orchestra and Spanish singer Luciana Elizondo. But the ambient aesthetic and dual mixes Chesky created for Graffiti Jazz will continue to define Meta-Dimensional Sound projects.

“Artists need to reinvent themselves,” he said. “I’ve done hundreds of records with two microphones, but I think with technology we can make it better. If people have a properly set up stereo, with the speakers and the listener in a 60-degree equilateral triangle and a properly treated room, the soundstage should be able to go way past 60 degrees and you should have height info. We’ve been locked into the stereo triangle for 70 years, and it’s time to do something else.”

. . . Brent Butterworth