When I turned in last month’s column, “What Playing Music Taught Me About Audio,” SoundStage! founder Doug Schneider replied, “I like it. But from reading the headline, I thought it was going to be about what you learned from recording your new album.” Fair enough—because actually recording, mixing, and releasing my first serious attempt at an album taught me a lot about audio and music, even after being deeply involved in both for decades.

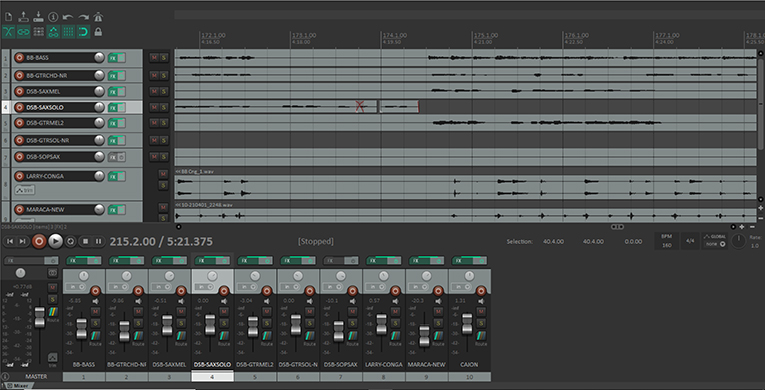

Like many recent albums, this one happened in large part because of the pandemic—saxophonist Ron Cyger and I, after losing all of our gigs, found ourselves passing the time by making YouTube videos. A fledgling Los Angeles record label noticed them and asked us to make an album. Although I’d been doing multitrack recording since the 1980s, this was the first major project I’d mixed with a digital audio workstation (DAW), which increased the complexity of the project by an order of magnitude or so. In the process, Ron played four different horns and used three or four different microphones, while I played two different double basses with four different sets of strings (and strings have a much bigger effect on the sound of a double bass than they do on the sound of a guitar).

The year I spent on this project changed a lot of my attitudes about music and audio. It’s tough to sum up everything I’ve learned, but I’ve condensed it into four principles.

1) Nobody really knows what a music recording is supposed to sound like.

I’ve always gotten annoyed when someone who had nothing to do with a recording project says they know what the recorded music is supposed to sound like, but my experience has made me even more dismissive of the idea. Especially since, even after mixing the album, I’m not even 100 percent sure what it’s supposed to sound like.

Every modern recording involves hundreds, maybe thousands, of little decisions that affect the sound: the instruments used, the way they’re played, the acoustics of the recording space, and the choice of microphones and mike placement. A DAW opens up the possibilities even more because you can add any of hundreds of different plug-ins for EQ, compression, reverb, delay, and special effects—each offering a wide array of options. Even the people who engineered and mixed the album probably can’t be entirely sure of what settings they used.

2) For musicians, sound is an eternal struggle, not a pristine creation to be preserved.

We see lots of ads proclaiming that an audio product “reproduces music as the artist intended” or “uncovers musical truth” or some such palaver—but the people who write this verbiage have little grasp of the reality of recording. Most artists consider their recordings merely the best they could do given the constraints on their time, budget, and patience. Often they’re happy with the result, but they probably also wince a little when they hear certain parts of a recording.

There’s a sense in some audio circles that a musical performance is a pristine, perfect event that must not be vitiated. The reality is, except for keyboard players—whose instruments are usually in a perfect state of tune, and whose touch usually changes only the volume of a note rather than the timbre or pitch—musicians constantly struggle to achieve the sounds they hear in their heads, and their recorded sound is just the best they could muster at the moment. Most instruments fluctuate in sound quality depending on the state of the instrument itself; its wear-prone components (strings, reeds, drum heads, etc.); the temperature; the acoustical surroundings; and the day-to-day, hour-to-hour, minute-to-minute shifts in the artists’ skill, mood, and physical limitations. Even the greatest artists have days when they sound the way they want to and days when they simply can’t get it working right.

The lesson here is that to most musicians, concepts like “musical truth” are silly. If listeners like the sound, the musicians are happy—no matter what gear the listeners are using.

3) Dynamic range compression isn’t evil—it’s a technical necessity.

Anyone who follows audio will often encounter audiophiles railing against the supposed evils of dynamic range compression—the reduction of the average-to-peak loudness ratio of the recording, or more simply put, making the loud parts softer and the soft parts louder. I’ve seen audiophiles claim that “compression sucks the life out of the music” and question the competence of the audio pros who use it. But if they tried to do a mix without it, I think they’d change their minds.

Most recordings are not pristine events but the best the musicians and the engineers could do that day. They’ll probably need some post-processing to sound their best, and compressors are key to this. For example, one of Ron’s sax tracks sounded troublingly harsh, probably due to a not-so-great microphone or non-optimal mike placement. I could have asked him to do it over, but he had plenty of other tracks left to record, and I figured I could find a way to get it sounding better. EQ’ing out the harshness made the sound dull, but using a multiband compressor tamed the troublesome lower treble without damping the top two octaves.

When it came time to mix, a simple LA-2A emulator plug-in helped keep all the instruments clear in the mix without jumping out too much on peaks, without running up against the 0dB maximum level, and without losing some of the little details that might otherwise get buried in a busy mix.

Sure, compression has sometimes been overused, but there’s a reason that pro recording, mixing, and mastering engineers use it: properly employed, it makes the music sound better. I encourage all audiophiles to download a free copy of Audacity and try experimenting with different compression settings on a variety of recordings, so they better understand what compression does and learn to identify by ear when it's being used appropriately and when it's being misused.

4) Mastering engineers do a lot more—and less—than you might think.

One of the real treats of this project was working with veteran mastering engineer Allan Tucker, who’s mastered somewhere around 3500 recordings, with a focus on jazz acts but also many major rock albums to his credit. Seeing several progressive jazz artists on Allan’s list of credits, I expected he’d be able to smooth out the many inconsistencies in our rather ramshackle recording—and I really knew I had the right engineer when he insisted on spending about an hour on the phone with me before he took the job, talking about the project and telling me what he needed me to do in the mixes to ensure that he could do the best possible job for us.

I had thought of mastering mostly as adjusting the levels and compression to get the average levels of the songs consistent and adding EQ tweaks to make the instruments sound consistent from tune to tune—and to serve as a “second set of ears” to catch the mistakes I suspected I’d made. It’s all that, but it’s much more, too.

“Mastering is a whole lot of little things,” Allan told me. For example, he insisted I leave the blank space at the beginning and end of each track—the “heads and tails,” as he called them—and let him trim the songs so that there’d be an appropriate pause after each one. A more intense tune might need a longer pause after it ends to let the listener recover. He also provided all the file formats and documentation we’d need to submit the album for digital distribution (to streaming services) and CD pressing. And he generously coached us on sequencing—i.e., determining the order of the tunes.

Ron and I were both a little shocked when we got the masters back. That’s partly because they didn’t sound that much different from the originals; the fundamental character of the mixes remained. The difference was that the instruments sounded more consistent from tune to tune without sounding homogenized. And all the levels sounded perfect—we never felt the need to adjust the volume when listening to the album. Simply put, my mixes sounded like good demos, but the master sounds like an album.

. . . Brent Butterworth