I got a surprising phone call a couple of weeks ago from a fellow audio writer working on an earphone review. He doesn’t review a lot of headphones or earphones, and didn’t know what to make of the latest review sample he’d received. “They have no bass at all. None. I don’t get it,” he said. I happen to have discussed this issue a few years ago with the manufacturer of these earphones, who told me, “I have a lot of customers who want that sound.” I’ve battled online with a few of them, who insist that headphones and earphones with elevated treble have more detail. I advised my colleague to write one of those “If this is the kind of thing you like, you’ll like this” reviews for which the old Stereo Review was notorious.

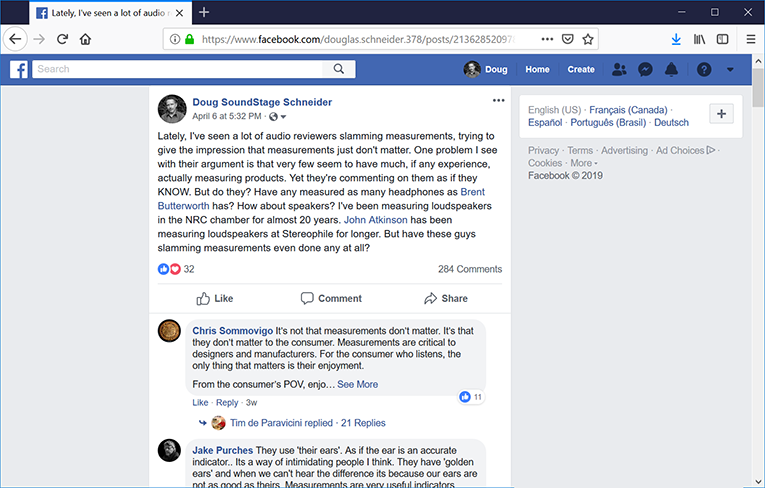

The issue emerged again the very next day, when SoundStage! founder Doug Schneider commented on Facebook about audio reviewers who are “trying to give the impression that measurements just don’t matter,” despite the fact that “very few seem to have much, if any, experience actually measuring products.” Predictably, his post garnered hundreds of comments and digressed into all sorts of sub-discussions. Just as predictably, I tossed in a few of my own observations, one of which was that thoughtless reverence for any subjective impression, no matter how casual and uncontrolled the listening circumstances or how uninformed the listener, has given rise to the notions that “any audio product, no matter how ineptly designed, is OK if some listener somewhere likes it,” and that “any opinion of any listener (including reviewers) of any product is valid.”

I was surprised to see John Atkinson, until recently the long-time editor of Stereophile (he’s now technical editor), comment that Stereophile founder “J. Gordon Holt used to refer to this as ‘My Fi’ and condemned it throughout his life.”

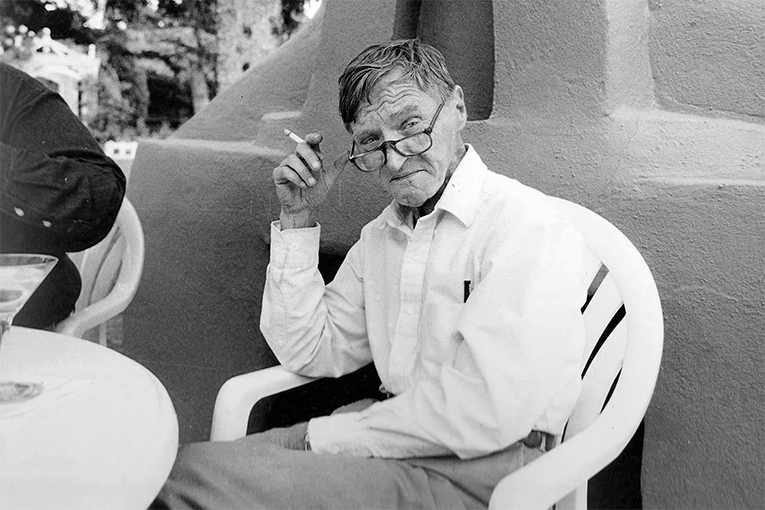

Holt had perhaps a greater influence on my thinking about audio than anyone. One of the most significant events of my early career was a night at an audio show in Miami in 1994, when he and I smoked and drank and talked audio until the hotel bar threw us out. So I was thrilled, once again, to hear a little bit of his philosophy -- and to learn a useful term that sums up much of what’s going on in high-end audio these days.

What’s going on, as I’ve observed from visiting recent audio shows and reading most of the leading audio websites, is a drift away from design principles developed and proven over decades, and more toward a “gut feel” approach to audio design. Designers are creating audio gear that expresses their own idea of what music should sound like, rather than seeking any sort of neutral or accurate reproduction of sound. It’s gotten to the point where many audio writers are railing against the very concept of accuracy, claiming that audio is purely a matter of opinion. Or as Gordon Holt derisively dubbed it: My Fi.

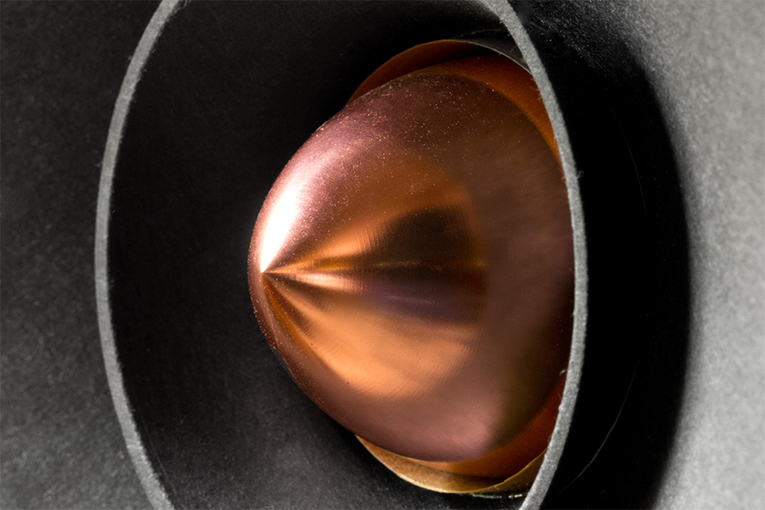

This has always been an issue with headphones. Not only do we have “audiophile” models with hyped-up treble to create the impression of added detail; we of course have bass-enhanced models that make every recording sound like Dr. Dre mixed it. Fortunately, both of those flaws can usually and easily be fixed with EQ. What’s worse is when designers start monkeying with the midrange to suit their personal taste, dropping in big dips and peaks wherever they personally think it sounds good. While S. Andrea Sundaram showed in a recent column that it’s possible to fix such headphones with EQ, you may need measurements (which aren’t always easy to find) to do so.

Why not just voice the headphones for natural sound in the first place? We have plenty of good research now that will dependably get designers safely into the ballpark of good sound. Audio manufacturers ignoring that body of knowledge because they think their personal ideas about headphone tuning produce a superior result might be a good marketing angle, but it’s unlikely to give their customers the best sound.

Examples of this trend in traditional, two-channel high-end audio include the new (or should I say old?) wave of single-driver speakers. The laws of physics dictate that these speakers will have ragged response and narrow dispersion at high frequencies. In their quest to follow the appealing yet ignorant “simpler is better” mantra, they substantially color the sound for the sake of nothing but a few dB of added efficiency.

Another example is amplifiers that intentionally add harmonic distortion. This may make music sound better in some ways; since the 1960s, guitarists have been using various devices to add distortion to their sound. But if the musicians, producers, and mastering engineers wanted extra distortion in their music, they could add it with the flick of a finger. They don’t need their judgment second-guessed by an amplifier designer who supposedly possesses some profound idea of what music should sound like.

If any listener wants more distortion, they don’t need to spend thousands on an amplifier to get it. They’re better off spending $449 on an Aphex Aural Exciter, which adds harmonics (i.e., distortion) in a much more controlled and adjustable fashion.

Rather than seeking high-quality, neutral music reproduction, many audiophiles now embrace cults of personality -- seeking out gear made or recommended by those whose taste they share (or more likely, whose statements best resonate with the audiophile’s self-image). This isn’t hi-fi. It’s pure My Fi. It reflects not an appreciation of music, but the opposite -- the desire to inflate one’s ego by imposing one’s own alterations on an artist’s work. The late (and much reviled) artist Thomas Kinkade cannily exploited this desire, equipping stores to customize prints of his paintings to customers’ taste by adding sparkly highlights.

J. Gordon Holt (photo by Steven Stone)

J. Gordon Holt (photo by Steven Stone)

The easy path for high-end audio enthusiasts, writers, and manufacturers is to pretend that we don’t know much about audio, and that My Fi is the best we can do. (Hey, they don’t have to read all those boring scientific papers!) But the fact is, we do know a lot about audio, and we do know a great deal about what technologies and engineering techniques will lead us toward more natural and satisfying reproduction of music. That’s the direction the audio industry should follow. I’m confident J. Gordon Holt would agree.

. . . Brent Butterworth