It never fails. Write an article about noise-canceling headphones for a mainstream publication, as my colleague Geoff Morrison did for The New York Times, and you’ll hear from readers about a variety of “hacks” for doing noise-canceling with better fidelity and/or for less money and/or to eliminate the dreaded phenomenon of eardrum suck. The most common suggestion is to use earplugs in conjunction with standard passive headphones. Others suggest using high-quality earphones and putting noise-canceling (or passive) headphones over them.

Clearly, those who tout these ideas are happy with the results they’re getting. But these claims will raise questions in the minds of anyone who’s paid much attention to headphone isolation measurements, which are a standard part of the testing process for most of us who publish headphone measurements.

Although the companies that make earplugs and noise-canceling headphones tend to cite a single number for the amount of noise their products block -- 32dB, in the example of some foam earplugs -- physics doesn’t work like that. No acoustical device (including acoustic treatments, earplugs, speaker stuffing, etc.) impedes or absorbs sound equally at all frequencies. In my measurements of earplugs and passive earphones, I’ve found that most provide far better isolation at frequencies above 1kHz than they do at lower frequencies.

The idea behind using earplugs with passive headphones is that you can reduce loud noises, such as airplane cabin noise, and still listen to the headphones you love. But when you add earplugs, those headphones will no longer deliver the sound you fell in love with. They’ll give you muffled sound that’s akin to what you hear when you throw a blanket over a speaker. While some readers may still find this an appealing alternative -- after all, foam earplugs can be bought in bulk for about 17¢ per pair, while noise-canceling headphones typically cost $200 to $400 -- I thought it’d be interesting to measure exactly how much noise reduction you get using these methods, and what effects they have on the sound of your headphones and earphones.

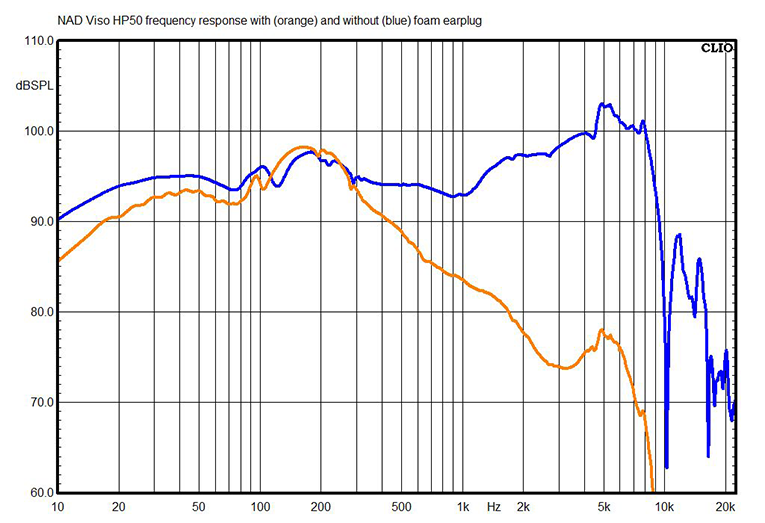

The first chart shows the effects of earplugs on the frequency response of NAD’s Viso HP50s, which are passive, over-ear headphones that I and some other reviewers consider one of the best for less than $300. The blue trace is the headphones’ response on their own, and the orange trace is the headphones when used with foam earplugs. (I don’t know the brand; it’s a generic pair that the Four Points by Sheraton Midtown hotel provides as a courtesy to guests who need more quiet than New York City can provide.) The mids start to roll off around 300Hz, and by the time you get up to 5kHz, the roll-off is extreme: -24dB. This will result in a sound that’s bassier and duller than the dullest-sounding headphones I’ve ever heard (which, for the record, are the JustBeats, a set of extremely bassy, Justin Bieber-endorsed headphones that Beats by Dre used to sell).

Just to be clear: This combination of passive headphones and typical earplugs absolutely will not deliver better sound than even a mediocre set of noise-canceling headphones. It’s not even close. Insisting that passive headphones with earplugs are better than noise-canceling headphones is very much like saying a live Yo-Yo Ma cello recital sounds better with your hands clamped over your ears. Acoustically, the effects are similar.

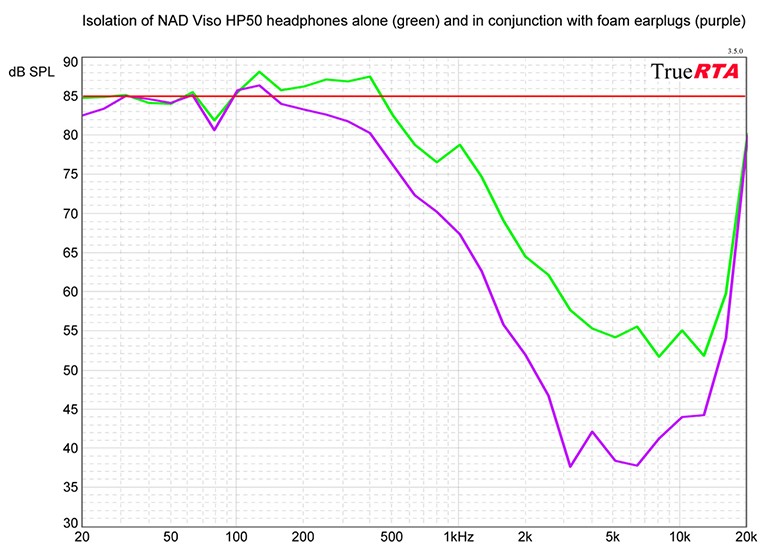

This chart shows how much extra isolation you get by adding earplugs to the Viso HP50s. The red line represents the reference: pink noise played through four speakers and a subwoofer at 85dBC. The lower the trace falls below the red line, the better of a job the headphones (or the headphones and earplugs) do of isolating your eardrums from outside sounds. As you can see, adding the earplugs doesn’t dramatically reduce noise in the “airplane cabin band” from about 100Hz to 1kHz. There’s no reduction at all at 100Hz, and only about -5dB at 1kHz. It doesn’t seem to me that the small amount of noise reduction gained by adding earplugs is worth the huge penalty paid in sound quality.

I will grant one possible exception to this statement, though. I recently tried using my custom-molded Sensaphonics musician’s earplugs, fitted with -9dB Etymotic filters, with a set of passive headphones on an airplane flight, and the result was OK. I still heard a lot more droning from the jet’s engines than I would have heard with good noise-canceling headphones, but the relatively flat attenuation of the custom plugs (they measure about -6dB at 100Hz, -9dB at 1kHz, and -18dB at 4kHz) did reduce some of the cabin noise without dulling the sound to an extreme degree. However, these earplugs cost $175 plus whatever your audiologist charges for making the custom earmolds (typically about $50), and you can easily find a good set of noise-canceling headphones for about the same price.

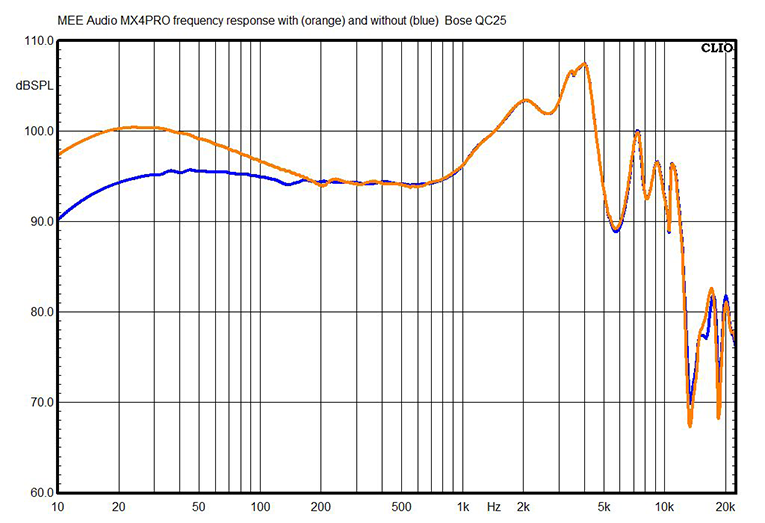

This chart shows the effect on frequency response of the other common method of reducing ambient noise without impacting sound quality: wearing over-ear headphones (either passive or noise-canceling) over a set of earphones. The earphones are connected to the source device (presumably your smartphone, or maybe an in-flight entertainment system), while the headphones are not connected to any source -- they’re there solely to block environmental noise.

In this case, I used the MEE Audio MX4PRO earphones. I measured them by themselves (blue trace), and worn with Bose QC25 noise-canceling headphones over the earphones. (I also measured this with the QC25s’ noise canceling switched off, but the result was the same as with the NC on.) Adding the headphones had only a mild effect on frequency response; the bass was boosted below about 170Hz, to a max of +6dB at 20Hz. This is a fairly benign effect, much like turning up the bass control on a receiver. It could make the sound too bassy, or it might actually make the sound better, depending on the earphones and your taste. You could easily counter this effect by dialing the bass down a bit in your smartphone’s audio control panel.

The point is, this technique preserves most of the sound character of the earphones. I found that it also seems to prevent eardrum suck. The QC25s’ eardrum suck is among the worst I’ve experienced, but I felt none at all when wearing the QC25s over the MX4PRO earphones.

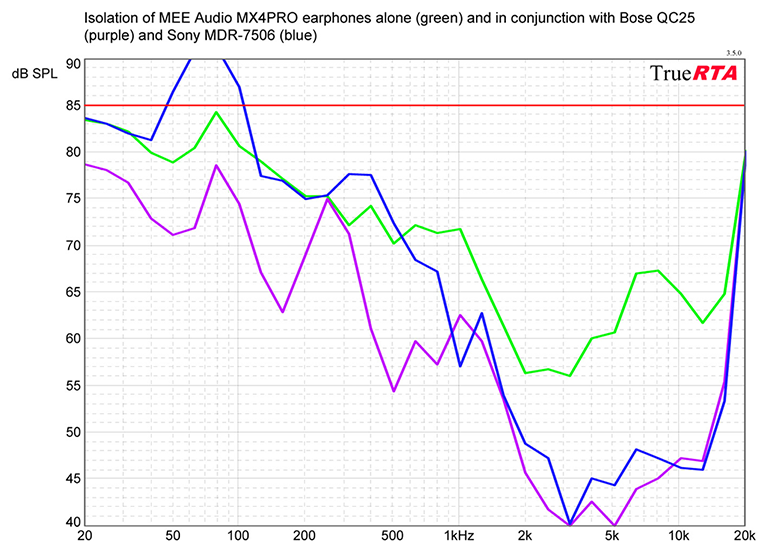

This last chart shows how wearing headphones over passive earphones improves isolation -- or does it? The green trace shows the isolation provided by the MX4PROs on their own, while the blue trace shows the isolation with Sony MDR-7506 passive headphones worn over the MX4PROs, and the purple trace shows the isolation with the Bose QC25s worn over the MX4PROs.

The MDR-7506 headphones deliver mixed results: They do attenuate more ambient noise at frequencies above 600Hz, but between 40 and 100Hz, and 200 and 300Hz, the chamber resonance of the Sony headphones actually boosts the noise level. But adding the Bose QC25 headphones substantially improves rejection of ambient noise in the “airplane cabin band,” by as much as 17dB at 500Hz. Like the Sony headphones, the Bose ’phones also improve ambient noise rejection above 1kHz by 5 to 15dB -- although there’s not much cabin noise above 1kHz, mainly just the hiss of the airplane’s ventilation system.

So it seems to me that if you want to enjoy true audiophile-grade sound on an airplane, using a good set of passive earphones in conjunction with noise-canceling headphones is a great idea. On the other hand, using earplugs with passive over-ear headphones is not going to give you anything close to audiophile sound quality -- but it would be a great choice if you want a good, cheap noise blocker for sleeping.

. . . Brent Butterworth