The recent closing of New York City’s Lyric HiFi—for decades, one of the most esteemed high-end audio dealerships in the US—portends a dicey future for the high-end audio industry. This doesn’t surprise me, because high-end audio has changed radically in the last 30 years. As I see it, the industry, while certainly capable of producing exciting products that deliver real improvements people would be happy to pay for, focuses too much of its resources on creating products that chase fads instead of pursuing innovation. I think high-end audio writers (and podcasters and YouTube influencers) are mostly to blame.

When I started writing about audio in 1989, big newsstand magazines such as Audio and Stereo Review dominated the press. These publications weren’t perfect by any stretch, but you couldn’t deny the chops of their technical editors. When a new audio technology hit, they’d publish comprehensive explainers along with in-depth reviews that ferreted out the pros and cons. Their editors demanded proof that new technologies and radical designs delivered a clear benefit to their readers. I got to know many of these editors, and I disagreed with them often. But as my experience grew, I realized they were usually right.

Audio writers and editors of this sort still exist, but in high-end audio, they are rare. Now, if a new technology comes along that delivers a demonstrable benefit, high-end audio writers are likely to denounce it. But if a manufacturer introduces a new product or technology with a backstory that panders to their beliefs and biases, they’ll endorse it, even if it can’t be demoed to advantage without listeners knowing what they’re hearing and being prepped with a persuasive sales pitch.

Silly things today’s audio writers fall for

Gurus: Many audio writers abandoned their critical thinking when the legendary engineer Bob Stuart launched MQA, a compression technology created to deliver high-resolution audio in a relatively low-bandwidth data stream. The initial public demos of MQA were so fishy that I have to think these writers were won over entirely by Stuart’s reputation. The first three demos I heard simply played MQA-encoded music through a top-of-the-line Meridian audio system without comparing it to non-MQA recordings. The fact that MQA sounded good on these systems means nothing, because any decently recorded music would have sounded great on these systems. Meridian reps proved that in a demo of a similar system a few years ago, when they dazzled the audience with a recording they later told us was a 128kbps MP3.

If you really had a groundbreaking technology, wouldn’t you launch it with level-matched, public A/B demos against the technology it hoped to replace? Years later, MQA still struggles to prove its worth, especially after a recent video highly critical of the technology, but the writers who fell for MQA’s “doesn’t this sound great?” demos aren’t backing down. Wanna bet that if you play them a 128kbps MP3 and tell them it’s MQA, they’ll rave about how great it sounds and chide you for “not getting it”?

Exotic materials and components: Innumerable unusual materials have been used in an attempt to improve audio products, particularly speakers and headphones. We also see rare componentry used in other high-end audio products. Some electronics manufacturers promote their exclusive caches of “magic” transistors that are said to deliver superior performance, yet are now discontinued and unavailable to manufacturers who weren’t wise enough to stash some away.

Many audio writers lead off reviews with lengthy descriptions of exotic materials and components used in the products under test, but no serious evaluation of the manufacturers’ claims. However, they don’t need to read Voice Coil or the Journal of the Audio Engineering Society to sort out truth from hype—they just have to use logic. Think about it: for all the advanced materials now used in speakers, an MDF box with a paper-cone woofer and a fabric- or aluminum-dome tweeter can still deliver competitive sound quality, and most of today’s best audio electronics are made largely from off-the-shelf components.

Outdated technologies: It’s fashionable in high-end audio to tout the superiority of technologies that debuted even before rock ’n’ roll was invented: single-ended triode tube amplifiers with rated power output of around 10W, often paired with super-efficient speakers that employ full-range drivers with whizzer cones, or strange-looking, hand-made horn drivers. These claims of superiority are not backed by controlled listening tests, only by the emotionally appealing yet utterly ignorant claim that “simpler is better.”

If audio writers who praise these products asked mainstream speaker designers why they don’t make super-efficient speakers, they’d learn that with efficiency comes compromises—in frequency-response linearity, dispersion, distortion, and power handling. Few highly efficient speakers achieve a respectably flat frequency response and broad dispersion. And many of the primitive tube amps that are typically used to drive them have very high output impedance, which will interact with a speaker’s impedance to change the sound in ways the speaker’s designer didn’t anticipate and likely wouldn’t condone.

(Paradoxically, in headphones, the latest fad is inefficient headphones, such as the HiFiMan Susvaras, but there may be some merit to this idea, and even the Susvaras need only a few watts of power.)

Useful things today’s audio writers reject

Room correction: I suspect every SoundStage! writer would concur with the idea that well-designed room-correction systems can yield the biggest improvements of any upgrade you can make to your system. Scientific studies have confirmed that these systems’ ability to analyze your room’s acoustics automatically and optimize the sound of your system to suit can produce significant advances in sound quality. You’re unlikely to find such studies supporting the benefits of any particular amp, preamp, or DAC design, much less accessories such as power conditioners and cables.

Yet most high-end audio publications review room-correction technologies about as often as they review Kiss albums. That’s probably because the clear benefit of systems such as Anthem Room Correction, Dirac Live, and Trinnov belies the “simpler is better” narrative. As a result, only a few brands of stereo components (notably Anthem, Arcam, and NAD) offer room correction.

Subwoofers: Getting good stereo imaging demands that you place your speakers in a triangle, with each speaker equidistant from your listening chair. But this isn’t the optimum position for the smoothest bass response, because room acoustics affect bass frequencies very differently than they affect midrange and treble. To get the best sound, you need speakers positioned to produce the optimum stereo imaging in the midrange and treble, and a separate bass speaker—a subwoofer—positioned for the smoothest bass response.

But again, this violates the “simpler is better” maxim, so few high-end audio publications take subwoofers seriously—and thus we rarely see subwoofer outputs incorporated into high-end audio gear (with Classé, Parasound, and the manufacturers mentioned previously being notable exceptions). High-end audio writers may protest this statement, claiming it’s too difficult to get a seamless blend between a subwoofer and stereo speakers, but home-theater enthusiasts routinely accomplish this task without much fuss (and room-correction systems do it automatically).

Science: Browse the Audio Engineering Society E-Library, and you’ll find audio research papers dating back almost 70 years. Some of this scientific research has been truly groundbreaking—for example, research into listener preferences has dramatically improved the quality of speakers since the early 1990s, and it’s starting to do the same for headphones. The blind listening tests on which these papers are typically based tell us much about what makes great speakers or headphones—and also about what changes in an audio system listeners can and cannot hear.

Yet many of today’s audio writers still reject this science, and some clearly have never bothered to read it. Their self-serving, totally unsupported narrative insists that only in casual listening tests, in which the listener always knows what products and technologies they’re hearing, can the true character of an audio component be divined. Unfortunately, this “method” often results in rave reviews of components (such as speakers with full-range drivers and tube amps with high output impedance) that exhibit huge, unnatural colorations that measurements and/or blind listening tests easily reveal.

I could go on—SoundStage! founder Doug Schneider and I both thought of many more examples when we first discussed this column—but I think I’ve made my point. I don’t see much future for a high-end audio industry in which the aesthetic standards are set by audio writers who rave about things that deliver no benefit or make the sound worse, and who ignore technologies that deliver an obvious, demonstrable benefit that anyone can appreciate.

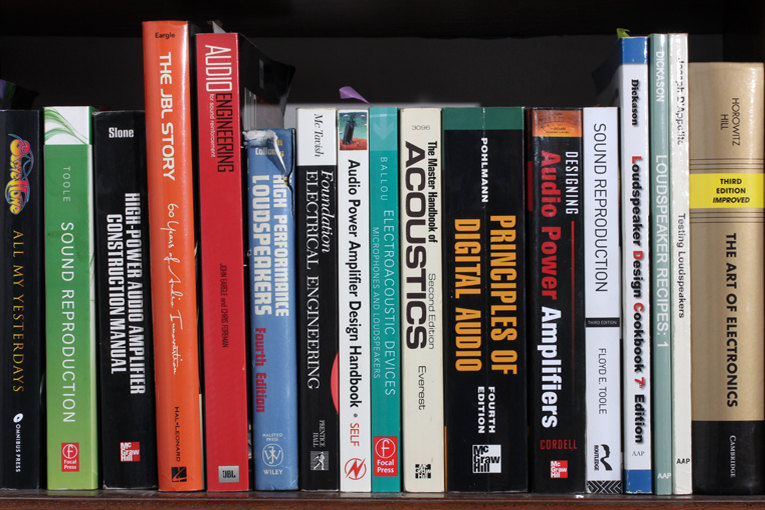

If high-end audio is going to survive, we need a new class of audio writers who, instead of lazily gathering haphazard knowledge of their field by reading technically lightweight, factually dubious opinion pieces in consumer audio publications, are willing to take on the challenging but rewarding task of learning how these products really work. We need writers who’ve maybe dug into such authoritative books as Vance Dickason’s Loudspeaker Design Cookbook, Floyd Toole’s Sound Reproduction: The Acoustics and Psychoacoustics of Loudspeakers and Rooms, Ken Pohlmann’s Principles of Digital Audio, and Bob Cordell’s Designing Audio Power Amplifiers.

In short, we need writers who have the knowledge to identify and promote products and technologies than can deliver a real benefit to their readers, instead of raving about stuff that does little or nothing to improve the listening experience.

. . . Brent Butterworth