A longtime audio-industry friend of mine, whose job straddles the consumer and pro audio realms, called me up a couple of days ago to thank me for my review of the HiFiMan HE400se open-back headphones. After seeing the review on Facebook, he bought a set out of sheer curiosity—they’re only $149 USD—and he actually considered my rave review something of an understatement. “I have headphones that are close to $2000 that don’t sound anywhere near as good as these,” he raved.

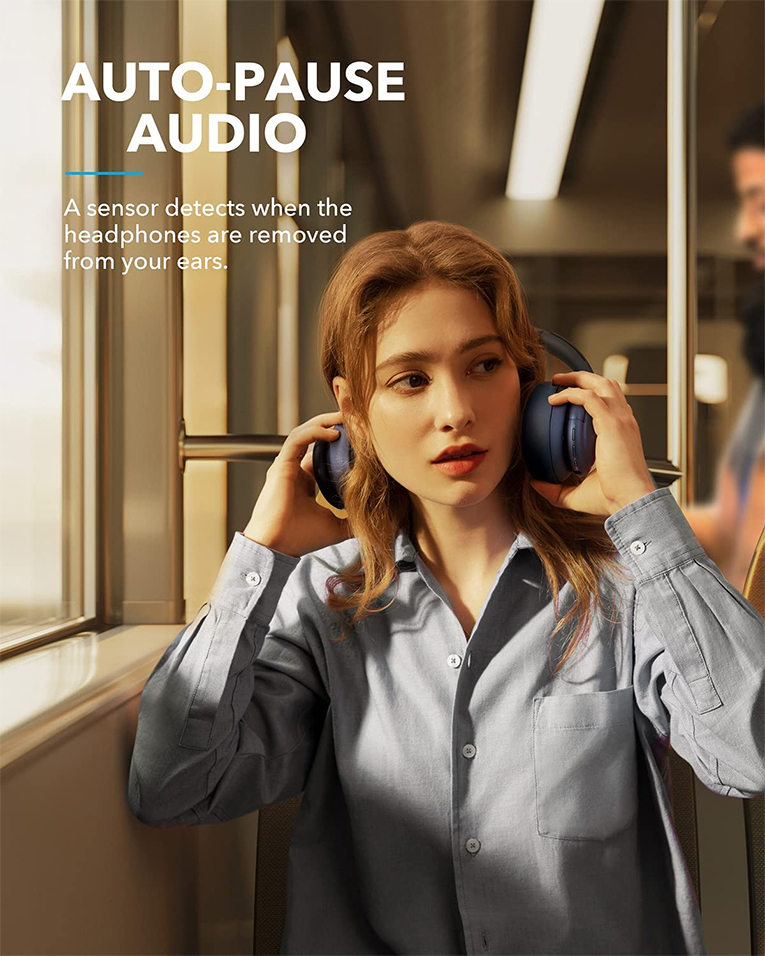

As I wrote my reviews of the HE400se’s and the Soundcore Life Q35 noise-canceling headphones—which are even less expensive at just $129.99 but just as much of a breakthrough in price vs. performance—I wondered how high-end manufacturers will respond, and if they can respond.

Of course, the high-end two-channel audio industry has survived and even prospered in the face of much less expensive competition. Despite the fact that you can get an excellent stereo amp for $1000 (or less) and extremely competent speakers for $500 a pair (or less), companies still make and sell amps that cost 50 times as much and speakers that cost 100 times as much. The advantage that traditional two-channel audio manufacturers enjoy is that they can add luxurious touches—much as the high-end watch industry does to snazz up its products, which are less accurate at timekeeping than my $99 Fitbit fitness tracker is. Sure, a more costly amp might have a bigger power transformer, higher-quality capacitors, and better internal grounding and shielding, but perhaps just as important, it’ll also look a lot nicer than the $1000 amp; most affordable models look more like something you’d see in a server farm than something you’d want to show off in your audio rack. That $50,000 amp may well have $5000 to $10,000 worth of custom-machined metalwork in its chassis—and that’s at the audio manufacturer’s cost.

While some headphones—especially the high-end models from Focal and Meze—really do look terrific and certainly cost more to make than the HiFiMan and Soundcore models I reviewed, there’s just not as much opportunity for high-end bling in headphones. In the headphone world, a great logo will do far more for your sales than expensive materials can.

With active headphones, it’s increasingly tough for high-end manufacturers—or even better-known mainstream brands such as Bose and Sony—to beat the budget models, especially with headphones like the Soundcore Life Q35 approaching and perhaps even matching the big names when it comes to design and fit ’n’ finish. The Life Q35 headphones have also pulled even with Bose and Sony on noise canceling. And if Soundcore puts some serious effort into its app—which offers 22 mostly horrible EQ modes when it really only needs two or three good ones—it’ll pull ahead of Bose and Sony. Slap a high-end brand on it, doll it up with a bit of leather and brushed aluminum, and sling some marketing BS about tuning by some mystical audio master, and you could sell them for $500.

In passive headphones, it may be even more difficult to differentiate high-end products. Most high-end passive audiophile headphones are just a driver in an enclosure, and the majority of them are open-back designs, which don’t even have much of an enclosure. Certainly, higher-end models can have better driver matching, but the HE400se headphones’ drivers are pretty well-matched, and I’ve found that the ear tends to be surprisingly forgiving of 1dB or 2dB errors in driver matching. And as much as manufacturers like to talk about the acoustical benefits of exotic materials, when I did my experiments measuring all sorts of variables in headphone design, I found that it’s extremely unlikely that enclosure materials will have an effect that’s within even an order of magnitude of what you’d get by making a minor porting adjustment or a slight change in the baffle or the earpads. While enclosure materials can make a difference in the sound of speakers, headphones aren’t speakers. Tiny headphone drivers produce very little acoustical power, and their small enclosures are relatively stiff, so resonances are almost never a problem and the enclosure materials are unlikely to have a significant effect on the sound—although, of course, beautiful bubinga headphone enclosures are almost certain to make you think the headphones sound better.

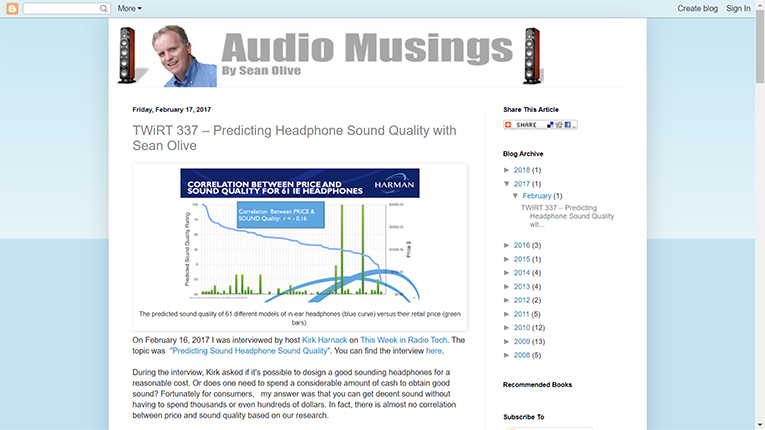

Four years ago, famed audio researcher Sean Olive of Harman International noted, in a study comparing frequency-response measurements of 61 earphone models with measurements shown in blind tests to correlate with good sound quality, that there was a slight negative correlation between price and sound quality. In other words, on average, when you pay more, you get slightly lower sound quality. (Frankly, based on what I’ve heard at high-end audio shows and what I know about speaker design, I wonder whether a similar study wouldn’t show a similar result for high-end speakers.)

Of course, despite increasingly fierce competition from budget models, the high-end headphone industry will live on—as do other luxury industries facing technological innovation. My hope is that, rather than launching not-really-better products that pander to audio writers’ biases against technological advances, high-end manufacturers will combine the organic approaches they’ve already mastered with powerful new digital technologies from Qualcomm and others, and create products that deliver a genuine improvement in headphone sound quality. Products like the Smyth Realiser show how much better headphone sound can be; it’s up to high-end headphone manufacturers to decide whether they want to explore such advances or wait for Soundcore to offer them for $129.

. . . Brent Butterworth