Headphones and smartphones have brought good sound to more people than high-end audio could ever reach. (Also, depending on the headphones, bad sound to more people than high-end audio could ever reach.) But headphones are also exposing billions of ears to sound—often very loud sound—for many hours a day. “Average people are now exposed to as much loud sound in the course of a day as audio engineers have been,” Jodi Sasaki-Miraglia, doctor of audiology and director of education and training for hearing-aid company Widex USA, told me.

I’d asked to talk with her because of my recent interest in hearing loss, inspired by work I’ve done measuring and evaluating hearing aids, personal sound amplification products (PSAPs), earplugs, and volume-limiting headphones—and also because my side gig playing jazz bass occasionally exposes me to potentially dangerous sound levels. Of course, most jazz gigs aren’t that loud, but sometimes in small venues I get stuck having to stand right in front of a P.A. speaker, and I occasionally play with octets and big bands that feature extremely loud massed horn sections—not such a problem if I’m at the back of the band, but if we’re all facing each other during rehearsal, it can be painful.

Although most people are probably aware that headphones can cause hearing loss, it’s not a topic I’ve heard headphone enthusiasts discuss much. But it’s an important issue. The World Health Organization estimates that by 2050, one in ten people will have disabling hearing loss, and nearly 50% of people between the ages of 12 and 35 are at risk of serious hearing loss due to excessive exposure to loud sounds.

All of the effort to prevent or moderate loud headphone listening has come through the mass market, with volume-limited headphones (mostly intended for kids), smartphone apps that track noise exposure, and true wireless earphones with hearing tests built into their accompanying apps. So audiophiles—who presumably spend a lot more time listening to music than most people do, and who probably listen at louder volumes because they’re typically more focused on the music—are on their own.

When I asked Sasaki-Miraglia what a safe level of listening for audiophiles might be, she replied, “It’s not so much about a ‘safe’ listening level; it’s more about healthy listening habits. Instead of thinking just about levels, it’s better to think about a dose—or how long you’re exposed to sound at a certain level.

“People talk about 85dB as a safe level, but that’s over an eight-hour day,” she continued. “When you go up to 90dB—just a little louder—you’re down to four hours a week. To really get to the point where you don’t have to worry much about hearing damage with long-term listening, you should really be at 75 or even 70dB.

“If you damage your hearing, you’re damaging the hair cells inside your ears that detect high frequencies, and they won’t grow back,” she cautioned.

There are some active (i.e., powered) headphones that limit maximum volume to 85dB, and some, such as the ISOtunes Free earphones and Puro Sound BT2200 headphones, even sound good—in fact, the BT2200s were among the first headphones with tuning based on the Harman curve, even before Harman actually started using the Harman curve. But audiophiles, by definition, are going to demand something better, so how can they assure their listening levels aren’t dangerously loud?

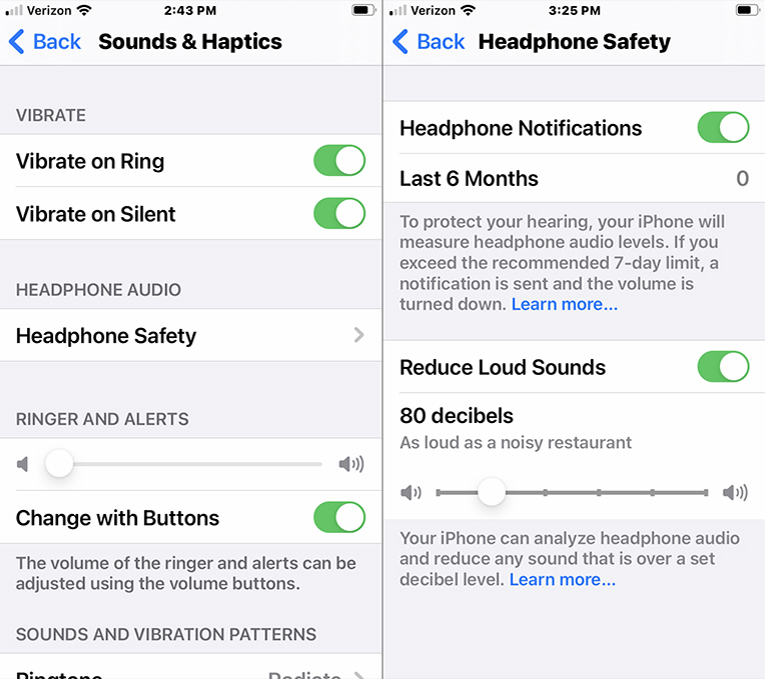

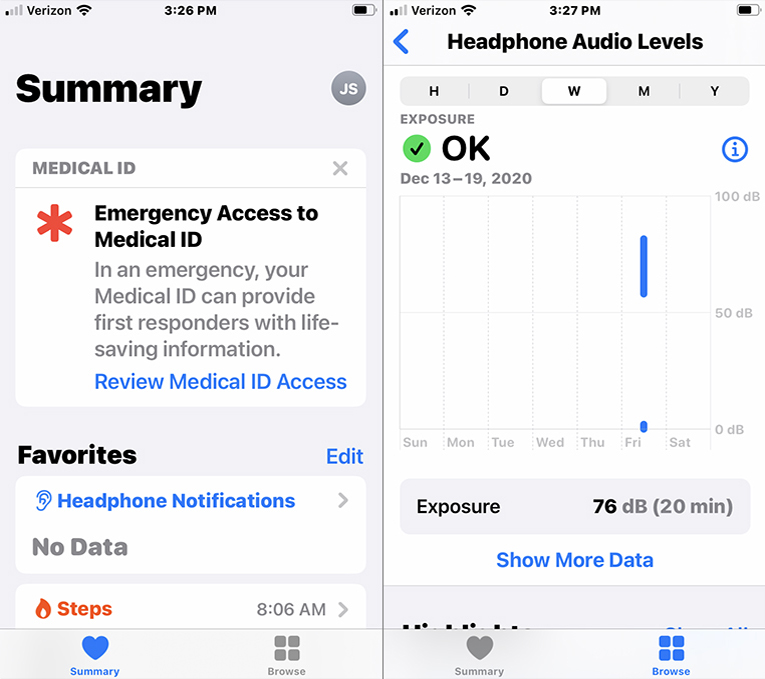

Sasaki-Miraglia is enthusiastic about Apple’s app used with earphones such as the AirPods Pro, which can set volume limits and tell you your dosage of loud sound over time. However, Apple can do this only because their apps “know” the characteristics of Apple headphones and earphones, and can thus accurately gauge the volume that’s reaching your eardrums. If you connect a different set of headphones—and especially if you use passive headphones plugged straight into an amp or mobile device—the app has no way to know what your listening level is. A specific voltage output may deliver a barely useable volume through, say, the HiFiMan Susvara headphones, but a dangerously loud level (36dB higher!) when connected to the Shure Aonic 5 earphones.

“It’s almost too bad that people’s ears don’t bleed when the sound’s too loud. Then they’d know when to back off the volume,” Sasaki-Miraglia said. “But if you’re listening loud enough to make your ears ring, it’s too loud. And if other people can hear your headphones [assuming they’re a closed-back design], it’s too loud.”

Another method I’d suggest—crude as it may be—would be to take a cheap sound-pressure level meter, set it for A-weighting and slow response, press it up against the baffle of your headphones, and play some fairly loud music that you like while watching the SPL meter. It won’t reflect the actual level of sound that reaches your eardrums, but it’ll give you a rough idea of the punishment you’re inflicting on your ears. If it’s around the mid-80s dB-wise, you should be reasonably safe for listening to a couple of albums every evening. If it’s below 80dB on average, then good on you. But if it’s in the 90-plus dB range, you’d be well-advised to back the level down. Otherwise, you could get to the point where you have a hard time telling high-resolution audio files from AM radio broadcasts.

“Hearing connects you with other people,” Sasaki-Miraglia said. “Nobody likes to be told what to do, but nobody likes to be embarrassed by constantly having to ask people to repeat themselves because you can’t hear what they’re saying.”

. . . Brent Butterworth