In the latest round of debate about MQA, I was dismayed to see the company once again tout its endorsements from mastering engineers. This is an “appeal to authority,” a common logical fallacy. It’s often seen in ads for audio products—the advertiser uses the endorsement of an authority figure (such as a musician or recording engineer) to supplement or substitute for marketing claims based on demonstrable features and benefits. Appeals to authority are even more common in promotions for things like books, movies, and countless consumer products.

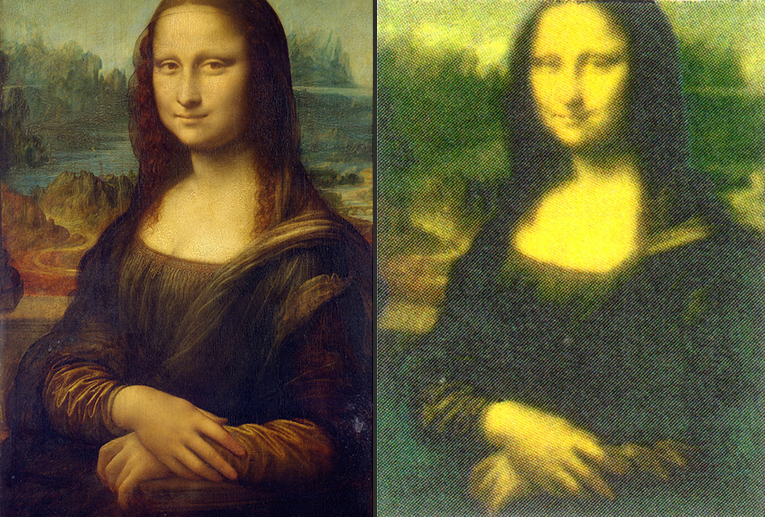

What’s wrong with a manufacturer touting praise from an expert? A recent article in The Wall Street Journal, “Why Apple, Amazon and Spotify Are Embracing Hi-Def Music: A Guide to ‘Lossless’ Streaming,” provides a great example. Right up in the deck, the article claims that lossless streaming is “vastly improving sound quality,” and it bases this statement in large part on comments from authorities. The article leads off with an anecdote from Emily Lazar, one of the world’s best-known mastering engineers, who likens the sound of typical streaming services (presumably meaning those using lossy compression) to visiting the Louvre to see the Mona Lisa, only to find “a photocopy of a photocopy of a photocopy of the painting, shrunken down to a postage-stamp size, and then photocopied again.” The article goes on to state, “She’s describing, in effect, what happens when the gargantuan, detail-rich music files she works with get shrunken down—or compressed—for streaming.”

I’m sure that if pressed, Lazar would acknowledge the hyperbolic nature of her statement. But The Wall Street Journal didn’t press her, and instead presented her statement as an accurate assessment—because she’s an authority.

Yes, as two decades of Audio Engineering Society papers show, listeners generally express a preference for uncompressed, 16-bit/44.1kHz audio compared with MP3 encoded at 128kbps, and trained and expert listeners can usually distinguish MP3 from uncompressed 16/44.1 at the higher data rates of 192 and 256kbps. But science doesn’t support the idea that there’s a dramatic audible difference between uncompressed and lossy-coded audio at any of the data rates commonly used by music streaming services.

Now here’s the Mona Lisa comparison mentioned before, with a 5000-pixel-high JPEG image of the painting on the left (resolution reduced to fit this web page), and an 8″ by 10″ high-quality print of that image, photocopied twice, reduced to postage-stamp size (1″ by 1.25″), and then scanned and restored to the same size as the original JPEG—the closest approximation I could make of what’s described in the WSJ article. (I did the printing and copying at a FedEx Office because their machines are a lot better than mine.)

You don’t need to be an art or graphics expert to tell which image is which. You don’t need anything brighter than candlelight to see the difference. It’s an extremely misleading exaggeration—even in a tossed-off, casual comment—to suggest that lossy codecs, at commonly used bitrates, have a comparable effect.

Mastering engineers are authorities on applying the appropriate EQ, compression, etc., to make music mixes sound their best and make albums sound consistent from tune to tune. Are they authorities in controlled A/B comparison tests of audio technologies? They might be, but it’s not their job. Did the mastering engineer’s opinion, in this case, emerge from a valid test, comparing a lossy streaming service to an original file, with the identities of the sources concealed and the levels precisely matched—or just from a casual listen? We don’t know. Does a mastering engineer possess a scientist’s understanding of what constitutes a judicious and technically supportable statement? Again, they might, but it’s not what they’re paid to do.

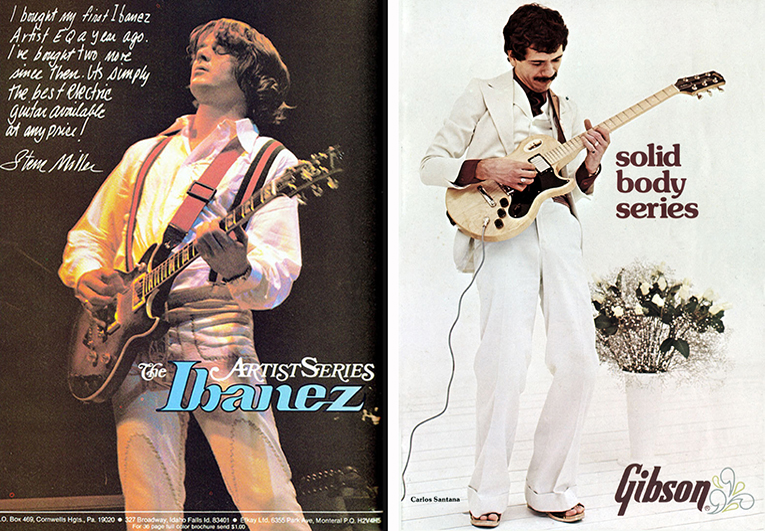

Appeals to authority also raise questions about the authority’s motives and conflicts of interest. In this case, it’s a Wall Street Journal story that promotes non-proprietary technology, and the authority is a world-famous Grammy winner who’s obviously not hurting for work, so there’s no reason to suspect a conflict of interest. But usually, it’s wise to wonder if and how the authority was compensated for their endorsement of a product or technology. I recently heard comedian Marc Maron ask musician Steve Miller why he used Ibanez guitars—at the time, a second-tier brand—in the 1970s, and Miller replied to the effect of, “Because Gibson and Fender wouldn’t give us anything.” Clearly, Miller’s endorsement didn’t mean as much as guitarists of the time might have thought. Nor did Carlos Santana’s endorsement of Gibson . . . then Yamaha . . . then Paul Reed Smith guitars, especially when you consider that no matter which guitar he played, he always sounded like Carlos Santana (which also suggests that no matter which guitar you play, you won’t sound like Carlos Santana). Even if no money or gear is offered, musicians and audio professionals will sometimes make endorsements in large part for the promotional value.

In headphones, it’s been common for musicians and audio pros to lend their names and endorsements to specific products. But again, we don’t know the terms of those endorsements. Years ago, when it seemed every headphone company had to have a model endorsed by a hip-hop artist, a friend in the headphone industry asked me to look over a draft of an endorsement contract they were preparing for a major hip-hop artist. I wasn’t surprised to see clauses regarding how the artist’s name would be used on the headphones, and how the artist would be compensated for their endorsement—but I was surprised to see no stipulation whatsoever regarding the artist’s approval of the headphones’ sound quality.

In fact, two of the worst headphones I’ve ever heard carried musicians’ names: the Justin Bieber-endorsed Beats Justbeats and the Simon Cowell-endorsed Sony MDR-X10, of which my colleague Geoffrey Morrison wrote, “I’d put money on the fact that Simon Cowell has never heard these headphones and possibly doesn’t know of their existence. If he does, or has, that gives me serious doubts about his ears.”

Appeals to authority aren’t necessarily without merit. After all, we’d surely respect a mastering engineer’s opinion of a set of headphones more than we’d respect the opinion of some random person off the street—or perhaps even more so, the opinion of Justin Bieber or Simon Cowell. I chose an Upton double bass in large part because Lynn Seaton—one of the most technically dazzling double bassists I’ve ever heard—plays one, and I figured any bass that works for him surely wouldn’t hinder my progress. I chose the iZotope Ozone 9 mastering plug-in for my digital audio workstation in large part due to endorsements from mastering engineers—including Lazar.

But in every case where we’re told we should like an audio product or technology because some authority likes it, we need to ask ourselves how qualified that authority is to make that endorsement, what their procedures were in determining the merit of what they’re endorsing, how the endorsement might benefit them, and whether a credible pitch could be made for the product or technology without relying on an appeal to authority.

I’ll close with a phrase copped from The New York Times columnist David Brooks, who gets paid the big bucks because he can express better in 14 words what I said in more than 1000: “Who you are doesn’t determine the truth of what you say; the evidence does.”

. . . Brent Butterworth