As I reported last month, the number of target curves for headphone and earphone response is growing. Honestly, I’m a bit dismissive of some of these curves. I’m fine with it if people like them, but based on my decades of communication with readers, I’m skeptical of the idea that any target response is a surefire prescription for listener satisfaction—although they certainly can serve as reference standards against which other models can be compared.

However, after hearing a description of the presentation about one of the target curves I wrote about, from the October AES Expo in New York City by Knowles R&D fellow Thomas Miller and electroacoustic engineer Cristina Downey, and then reading the convention paper, “A Wideband Target Response Curve for Insert Earphones,” I figured the Knowles project deserved more of my attention. And, best as I could muster, some attempt at confirmation.

Knowles pursued its research in part because the research behind the Harman curve—today’s most famous headphone response target curve—was conducted with a standard, so-called “711” ear simulator, which delivers valid and consistent measurements up to only 8kHz. About five years ago, audio-measurement companies started to offer headphone-measurement gear with internal damping that allowed for consistent measurements up to 20kHz, and sometimes higher. Knowles employed this gear—specifically, a GRAS RA0401 coupler, a variant of the RA0402 coupler I use—in conjunction with extensive listening tests to find out whether the Harman curve (which Knowles considered valid within its limited frequency range) could benefit from modifications in the upper octave of treble.

The research—which, by the way, focused on earphones and included no discussion of headphone response—concluded that listeners prefer a flatter treble response than the Harman curve describes. Younger listeners (age 22 to 35) preferred a response where the upper octave of treble was roughly equal in energy to the Harman-curve response at 1kHz. Older listeners preferred more high-frequency response; the oldest group measured, ages 56 to 65, preferred treble response roughly equal in magnitude to the Harman curve’s 3kHz response peak. The research suggests listeners want more treble boost as they age, roughly an additional 3dB for every ten years over age 30.

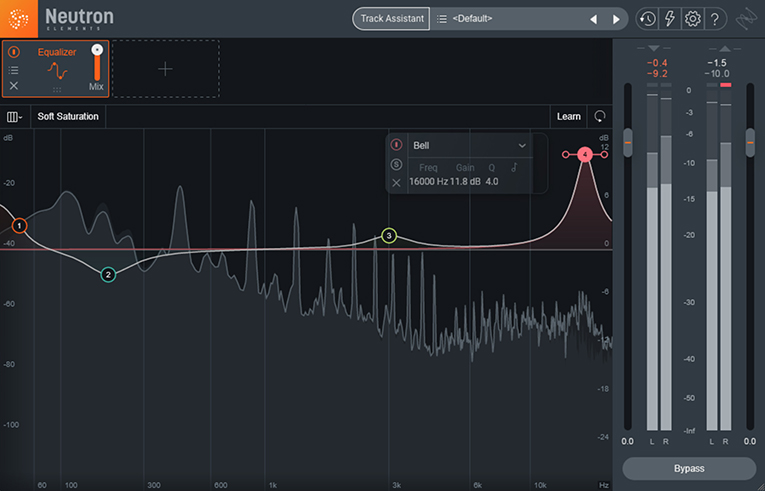

Specifically, the Knowles paper recommends a boost at 16kHz with a Q of 4. The older the listener, the more boost it recommends. Because the preference for the amount of boost differed with listener age, the authors suggest it might be a good idea to make the boost adjustable in an app.

I should note here that Knowles is best known as the leading manufacturer of balanced armatures—the drivers most commonly used in high-end earphones, and often used as high-frequency drivers in conjunction with dynamic drivers for the bass. Achieving the big treble boost the paper advocates is difficult with dynamic drivers, which tend to have less treble sensitivity than balanced armatures. So Knowles has a vested interest in promoting the necessity for extended treble response, and therefore the need for balanced armatures. That said, we have to judge the work by the quality of the science, not by who did it.

As an older listener (age 60), I was especially curious how the Knowles recommendations would work for me. The best method I could figure out to test them was to take a good set of earphones with balanced armatures and a response that’s not too far off the Harman curve—I chose the Meze Rai Pentas—and then equalize them a bit to get them as close to the Harman curve as I could . . . and then try the 16kHz boost Knowles prescribes with some of my favorite test tracks. I used an EarMen Eagle DAC-amplifier, feeding a Musical Fidelity V-CAN headphone amp, to ensure I’d have enough headroom to get the needed signal boost without forcing the amp into distortion.

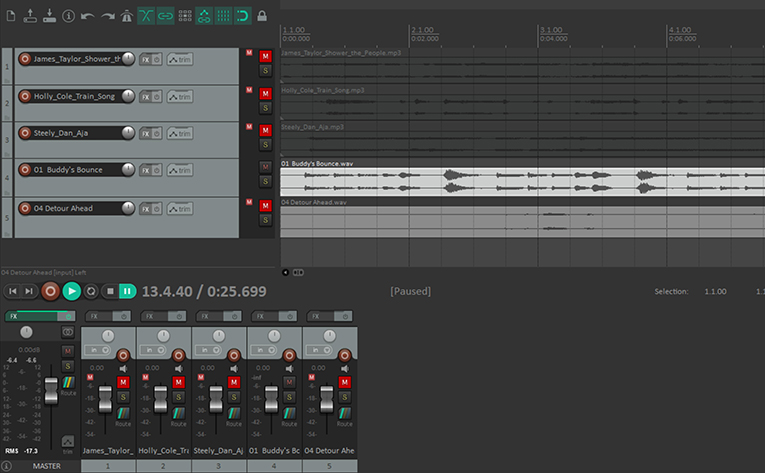

To get the exact frequency and Q Knowles prescribes, I loaded several favorite test tracks into the Reaper digital audio workstation and then ran iZotope’s Neutron Elements mastering EQ plug-in on Reaper’s main effects bus and in the effects bus of each stereo track. This cascading of the plug-ins was necessary because Knowles recommends 12 to 27dB of boost for my age group, and the plug-in provides a maximum boost of 15dB. Neutron Elements let me dial in the EQ needed to get the Rai Pentas adjusted to the Harman curve, and also let me set a filter for the exact 16kHz (Q of 4) response described in the Knowles research. I was then able to adjust the amount of 16kHz boost to my liking.

I included both MP3s and uncompressed WAV files because most of what people listen to nowadays is data-compressed. The recordings I used were James Taylor’s “Shower the People” (256kbps MP3, ripped from the 16-bit/44.1kHz stereo track of the Live at the Beacon Theatre DVD, Sony), Holly Cole’s version of “Train Song” (Temptation, 256kbps MP3, Capitol / Metro Blue), Steely Dan’s “Aja” (Aja, 256kbps MP3, ABC), Camille Thurman’s version of “Detour Ahead” (Inside the Moment, 24/96 WAV, Chesky), and “Buddy’s Bounce” from my own album Take2 (16/44.1 WAV, Outrageous8 Records).

Typical of the difference I heard was on “Shower the People,” which has prominent acoustic guitar and glockenspiel; with the boost at about 18dB or greater, I definitely heard more presence in these instruments, and the boost added some liveliness to the overall mix without making it excessively bright. My results were similar on “Train Song” and “Aja.” On the Camille Thurman recording, “Detour Ahead,” the boost exacerbated the already too-prominent brushed snare drum, which I found intolerable; the root of that fault is in the recording, but this made me realize you’d definitely want an “off” switch on such a relatively extreme EQ.

Hearing “Buddy’s Bounce” with the boost set between about 18 and 25dB was a kick. It didn’t change the character of the tune; it just made it sound a little more exciting. I’m actually inspired to try a few dB of boost at 16kHz in my mixes going forward.

Of course, this was a very limited test because I’m not a researcher; I’m a reviewer who bangs out about 15,000 words a month. But I heard enough encouraging benefits to the “Knowles curve” that I think it stands a decent chance of having an influence on the industry. Let’s see what the feedback is as more people try it out for themselves.

. . . Brent Butterworth