Features

- Details

- Written by: Brent Butterworth

Two recent experiences have reminded me of an old and very important lesson about audio I and many thousands of other audio enthusiasts learned decades ago. But the lesson seems mostly forgotten. The first experience was a couple of “run-ins” with other audio writers -- one directly, on Facebook, and the other indirectly, through an editor friend of mine. The second was recording and mixing I’ve done for what will soon be my first jazz album: a collaboration with saxophonist Ron Cyger under the name Take 2.

- Details

- Written by: Brent Butterworth

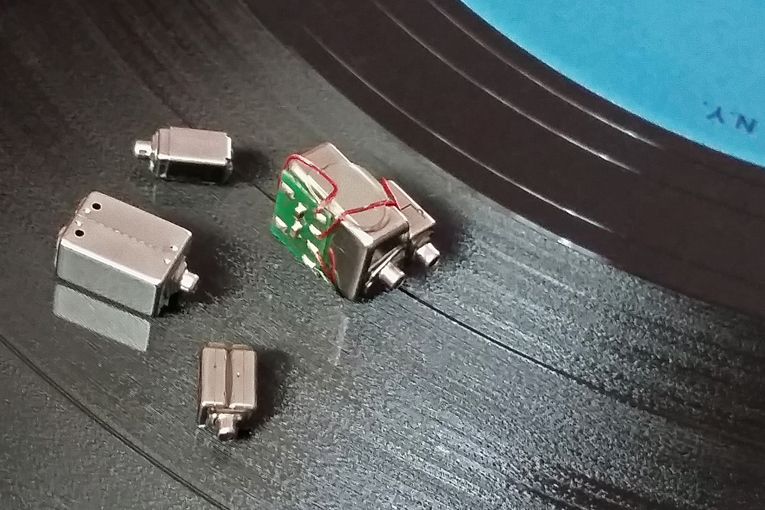

With a few rare outliers excepted, there are two different types of earphone drivers: dynamic drivers and balanced armatures. Although great earphones have been made with either type of driver, and often contain both types, the two drivers are very different in form and performance. Most headphone enthusiasts understand the concept of dynamic drivers, which are basically just miniaturized versions of conventional speakers, but many do not understand how balanced armatures work, or what their advantages and disadvantages are.

Read more: Balanced Armatures: Why You Might (or Might Not) Want Them

- Details

- Written by: Brent Butterworth

I think I just heard the future of headphones -- and I wasn’t really even listening to headphones. Technically, the product I was listening to is a PSAP, or personal sound amplification product: the Nuheara IQbuds2 Max, which I’m measuring for a technical publication along with some other PSAPs. The Nuheara IQbuds2 Max earbuds ($399 USD) are basically a set of true wireless earbuds with features added for hearing enhancement. Like many audio products that have come before them, the IQbuds2 Max earbuds seek to adapt their output to best suit the listener’s hearing characteristics. The difference is that this product actually seems to work.

- Details

- Written by: Brent Butterworth

My column last month, “The Biggest Lie in Audio,” sparked lots of commentary, but it also raised questions that are tough to answer. While most of the people commenting on the article here and elsewhere found it to be a welcome relief from what some have called the “faith based” approach of many audio publications, some weren’t so complimentary. A few derided science-oriented, “objectivist” writers as “narrow-minded” because they criticize audio products that don’t conform to generally accepted performance standards. Some insist that there’s no such thing as “accuracy” (they always put that word in quotes) in music reproduction, so audio writers have no basis on which to criticize outlier products.

- Details

- Written by: Brent Butterworth

You can’t get far into an audio forum or the comments sections of audio websites without encountering the statement “Some products that measure well sound bad, and some products that measure poorly sound good.” Depending on who said it, it’s at best uninformed and at worst a lie. And it’s a lie that sometimes sticks listeners with underperforming audio gear.

- Details

- Written by: Brent Butterworth

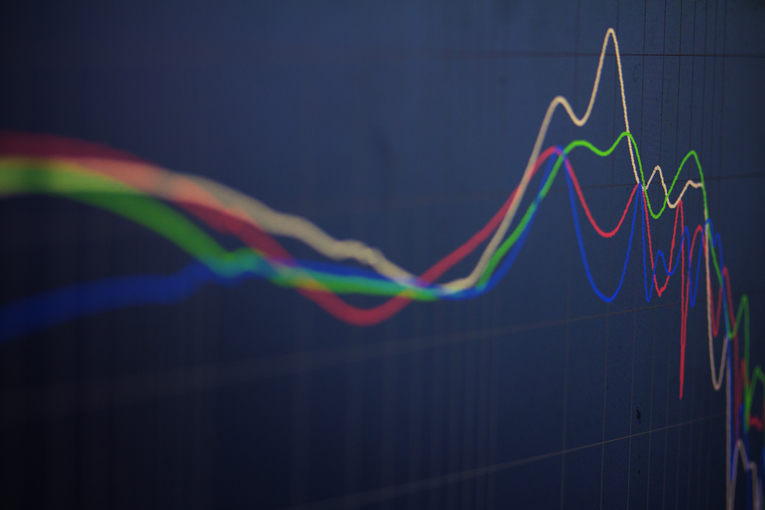

A decade ago, there was little consensus on how headphones should sound. With different brands -- or even different models of the same brand -- headphone enthusiasts rarely knew what to expect because they had only vague ideas of what was “right.” It’s a different world now, though. Thanks to scientific research (such as that behind the Harman curve), wider publication of headphone measurements, and more interaction between engineers at events such as the AES International Conference on Headphone Technology, good headphones have become common, rather than rare exceptions.

Read more: Voicing Headphones, Part 2: HiFiMan’s Fang Bian and Focal’s Mégane Montabonel

- What Will the Next Generation of Headphones Be Like?

- How Far Have Headphones Come?

- Voicing Headphones, Part 1: PSB/NAD's Paul Barton and Dan Clark Audio's Dan Clark

- How Will Headphone Testing and Reviewing Change in the 2020s?

- What the AKG K371 Headphones Tell Us About "Slow Listening"

- Where Are We At With The Harman Curve?

- Why Headphone Amps Are More Interesting Than Speaker Amps

- 2019’s Most Important Headphone Presentation

- Noise Canceling Is Much More Complicated Than We Thought

- How Does Aging Affect Audio Perception?

- Noise-Canceling Headphones for 17 Cents?

- Is Chesky Dumping Binaural?

- Why My Fi Ain't Hi-Fi

- Latency: A New Concern for Audiophiles?

- How to Read Our Headphone Measurements

- Eardrum Suck: The Mystery Solved!

- Should Audio Gear be Considered Luxury Goods?

- Headphone Equalization Using Measurements

- Why Is It So Hard to Rate Headphones?

- Five Things Headphone Enthusiasts Get Right (and That the Two-Channel Guys Get Wrong)

- The Best Possible Way to Test Audio Products (and Why Most People Don't Do It)

- Will aptX Adaptive Improve Headphone Sound?

- Is the miniDSP EARS the Death of Headphone Measurement? Or its Savior?

- What Are Measurements Good For?

- How Much Noise Do Your Headphones Really Block?

- Why We're Launching "SoundStage! Solo"

SoundStage! Solo is part of

All contents available on this website are copyrighted by SoundStage!® and Schneider Publishing Inc., unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved.

This site was designed by Karen Fanas and the SoundStage! team.

To contact us, please e-mail info@soundstagenetwork.com